How to Use The Theory

- Introduction to Conceptual Labor Analysis

- Conceptual Labor Analysis vs What We Already Do

- Conceptual Labor Analysis in a Nutshell

- Example: How to Do Conceptual Labor in the Woods

- CLA of Our Example

- Case Study: What is Programming?

Introduction to Conceptual Labor Analysis

The terms and Tenets of the Theory can help us identify and describe our conceptual labor, but it cannot tell us how to do it or how to do it better. Luckily, there is a simple formula for successful conceptual labor:

Foolproof Instructions for Successful Conceptual Labor

First, completely understand the situation. Then do the right thing. Next, completely understand the new situation. Do the new right thing. Repeat until done.

The catch is that if you do completely understand the situation, and you can do the right thing, then you don’t need to do conceptual labor. narrative that will work for you. You have discovered a conventional narrative that will work for you.

Conceptual labor is what we do in the absence of such reliable instructions. It’s what we do to understand the significant circumstances of difficult problems as they change so that we might do the “right thing” at any given moment.

The simple act of starting a job with an idea of what needs to be done, only to realize you must do things differently after beginning, is the fundamental pattern of conceptual labor.

This is self-reflective labor, in which we must come up with good questions as well as good answers. We must interrogate not just the materials of our labor but the conditions and structure of it as well.

We have to ask questions like children do – responding to a good answer with another “why?” What are the relevant circumstances of our labor? How do we know we understand them? When have we learned everything we need to, and how do we know we have? Has the situation changed since we began trying to understand it? Does what and how we see affect what we can know? What important information cannot be described in words? Did we do the right thing, or just the thing that felt right? Is it still the right thing, or was it just the last right thing? Is it right at all, or just less-wrong? How much less-wrong? And so on.

The Theory provides a framework in which to ask these questions. The Tenets propose the following approach:

- We can represent our experience of doing a job (our labor) with components that we can place into three basic categories: work, actors, and context.

- We encounter our labor through our own, individual ideas about it.

- We cannot “just do our work” if components in all three categories are connected and changing.

- Our work will proceed towards the goal of having a solid description of the job so we can “just do our work”.

- But as long as #3 is the case, we have to continue defining and redefining the terms of our job.

- While that is the case, we will have to also do the work of understanding and justifying new terms, approaches, and work.

- We can learn what to do in unknown situations by working on specific problems that teach us ways of working

Using the theory to analyze our labor, then, should provide a way to clearly define models and the relationships between their components to our own satisfaction. Doing so should help us become aware of significant changes to any of the components, or help reveal where our definitions were wrong. We should be able to repeat this process until it produces an understood model with static components that we can use as a set of instructions. This process should also allow us to infer broader principals and lessons from the answers to specific questions.

Conceptual Labor Analysis vs What We Already Do

As Tenet 7 reminds us, we end up following our own ad-hoc version of this process simply by doing our work and thinking carefully about it. Asking questions grounded by the specificity of our work will produce broader, abstract questions during conceptual labor. So why introduce a separate term for Conceptual Labor Analysis? Doesn’t conceptual labor imply self-considering work?

It’s true – many fields contain wisdom and habits that their practitioners can employ to productively critique their labor as they do it. (See the earlier chapter, We Are Always Writing Theories of Conceptual Labor.) For those of us with specialties, the terms of our art will likely be the most useful and convenient tools most of the time. Math, for example, offers tools like “zero”or “division.” More importantly, they are provided as part of a framework that relates them to a host of other tools, endowing in them a rationality that allows us to use them in almost any context where we encounter nothings or portions. This is what disciplines offer. Dance, for example, can ask and answer questions with movements of the human body. They may not be easily translated into English, but we can recontextualize what we absorb from a dance performance (or practice) whenever we deal with limits, or balance, or space.

However, even within the framework of an established discipline, we can encounter questions we don’t know how to ask, let alone answer. In fact, these are the questions that many people head straight for, whether mathematician or dancer. Sometimes breaking out of the work you know is the work. Whether our project is to learn a language for ourselves or invent a new one for the world to use, if we are to expand the frameworks we know, we must abandon them to some degree. Whether we are redefining our understanding of a personal project or rewriting the rules of a whole field, we must do conceptual labor to break new ground or enter the unknown.

When we exceed the limits of our current working language, the Theory offers us a neutral vocabulary. When we need to take a big step back and take another look at things, it means to give us more space to stand in, wherever we’re coming from. This is the main point of thinking about the Theory at all.

One of the central propositions of the Theory is that the mental effort to break new ground and enter the unknown is significant conceptual labor for the individual doing it, regardless of what they are working on or how well-educated they are about their subject. When we have a model of what we are doing, and we must change or otherwise interrogate that model, the internal, mental process to do so is functionally similar whether that model represents a task on our to-do list or the fundamental laws of physics. It follows, then, that it could be useful to have a universal, scalable method for examining this process, one which treats the process as inherently worthwhile, regardless of the subject matter it is being applied to.

Conceptual Labor Analysis, then, is what we will call it when we specifically use the terms of the Theory to describe our labor. It is not meant to replace the existing methods and terminology with which we do conceptual labor. It is offered here as a demonstration of the principles of the Theory, and as something to practice that may help us become more adept with our preferred methods and more aware of the structure of our habits.

While you must learn a little new terminology to use the Theory, it has been written in as plain language as possible. It should support our domain-specific language in clarifying our labor, and then quickly get out of the way.

In terms of the Theory, departing from one idea of “what I should be doing” for another implies a comparison and analysis between different models (or states of the same model). While there are many ways in which doing conceptual labor involves analysis, in terms of the Theory we would describe this essential process like so:

An actor reflects on their labor to compare the components of different models.

Conceptual Labor Analysis focuses on describing the composition, relationships, and functions of models and their components according to how a particular actor perceives them. When we reconsider our labor on these terms, we can sidestep, for a moment, the opinions of our profession, the meaning of its terminology, and our stake in any disagreements about those meanings. We can break from our trained responses, functional fixedness, and our unseen assumptions. Instead, we can encounter work as it is, in front of us, in this very moment.

So, in analyzing our labor, we may not always be able to anticipate the right questions and answers, but we can familiarize ourselves with the process to ask and answer these questions with more ease, insight, and precision. To that end, this section outlines the basic process of using the language of the Theory as an analytical tool.

Conceptual Labor Analysis in a Nutshell

All work changes. Even very simple work – the kind of thing we call “legwork” – can contain surprises and challenges. Our experience of these changes is what defines our labor. Put simply, conventional labor is what we do when we don’t have to think critically about these changes, and conceptual labor is what we do when we must. We need models when the conventional narrative fails us. Conceptual labor analysis begins by creating a model of labor.

Conventional vs Conceptual Labor: context is everything

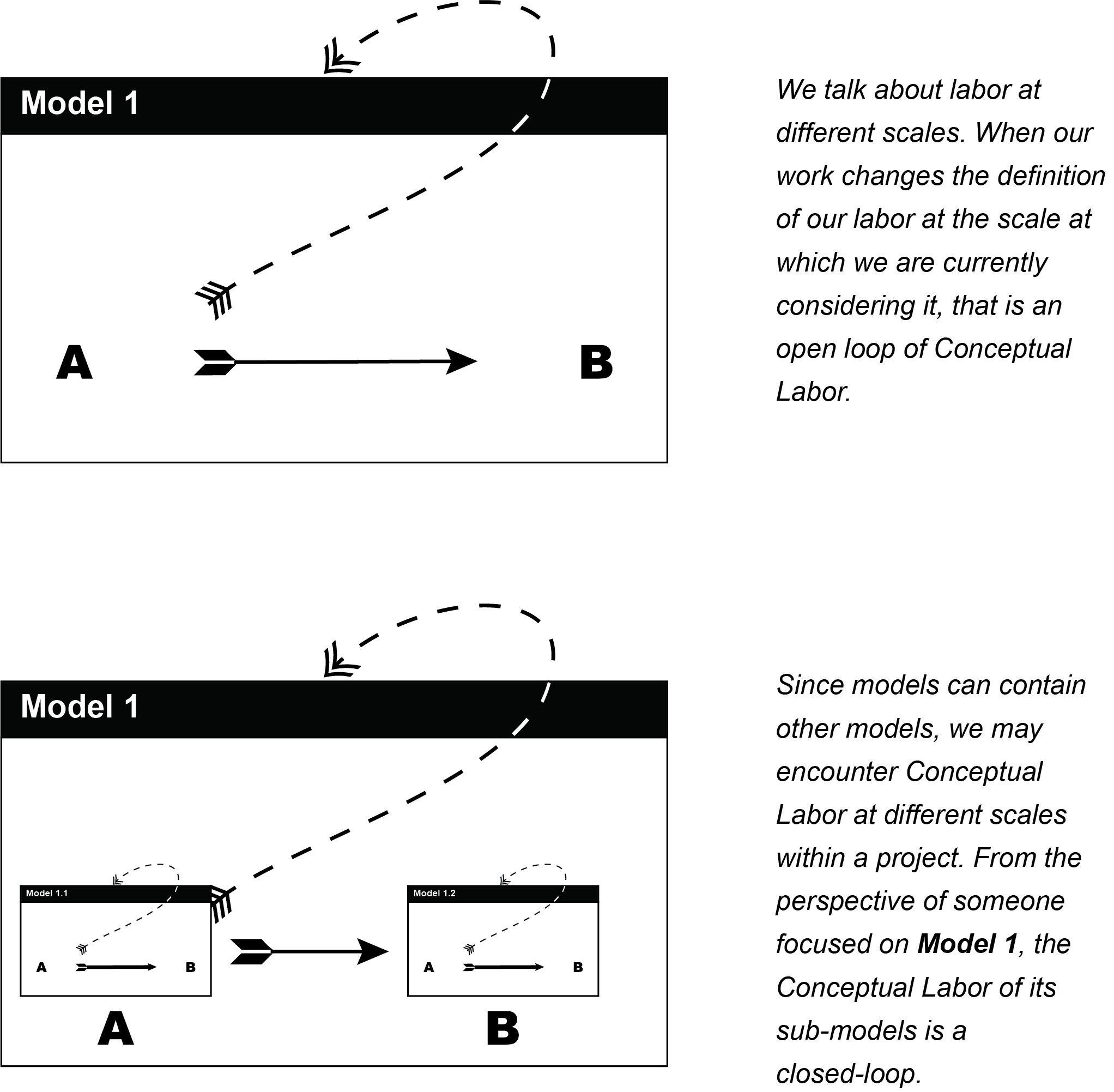

We may encounter challenges in the process of following clear directions that haven’t been explicitly called out, but unless those challenges fundamentally alter the definition of the project and our labor, we do not need to include them in our model. In the self-modifying “loop” of conceptual labor, we can think of this kind of challenge as a closed loop.

Whether those challenges do change our model is a matter of what we are doing. More precisely, in the terms of the Theory, it matters what context contains our work at the moment we consider it. By definition, conventional labor is what we do when we don’t have to consider our context – our context will be defined by the conventional narrative that we began with. If the circumstances have changed in such a way that we have to completely shift our focus from the stated goal to whatever is happening in that moment, we have changed our context and, in so doing, must do conceptual labor to get back to our original project. We must consider what we are doing not just on its own, but also how it relates to a broader, containing context.

Example: One Wrong Step

Anyone who has taken a wrong step while hiking and realized it mid-fall has been aware of how quickly one can shift between conventional and conceptual labor. If, while we are happily hiking along, we step on a rock we did not see and pitch over, the consequences of this challenge can re-define our labor. If we are injured, we can no longer follow the directions as written, and may have to redefine our project as “Get out of the woods safely.” But if we just can get back up, dusty but unscathed, the original project and narrative to complete it remain intact.

We could consider our racing thoughts mid-fall to be conceptual labor, because the outcome of the fall is unknown. We completely depart from the parent project for a split second to consider sub-projects such as “Plan how to deal with an injury”. But if that context is only temporary, and we immediately return to the original project, it is a closed loop of conceptual labor. In the scope of our original project, we are still doing conventional labor.

So with this in mind we can develop a sense of what to put in our models. They only need to be detailed enough to describe the fundamental qualities of our project at our current level of focus – the project that remains an open loop.

Step 1. Create a model of your labor

Describe, to your own satisfaction, what you mean to do. This names your project.

Assign actors, work, and context to anything that fits the strict definition of those components at the scale of your project.

For each component, consider how it is capable of altering the state of every other component during the course of labor.

Once you have created relevant models you can move on to the next step.

Step 2: Analyze and Compare Models

In conceptual labor analysis, the point of modeling work is to critically assess the composition of your models, and to compare different models or states of the same model. The important verbs of conceptual labor analysis are

- expand

- articulate

- navigate

- discern

Projects often start as a monolithic idea built on assumptions, prior knowledge, and deeply-held models of how the external world behaves. Breaking one’s initial idea of a project into a detailed model is in itself a form of critical analysis. Sometimes this is all we have to do to realize what we need to be doing differently. A lot can be accomplished simply by consciously considering each piece of our labor and how they all fit together.1

The “analysis” part of Conceptual Labor Analysis doesn’t just happen when we compare existing models. Significant analysis also goes into trying to precisely describe the model in the first place.

When we try to describe a project by its fundamental components, remembering that they must be essential to the stated project we can confirm that we are actually working in the context we say we are, or realize that we are focused on something else. One outcome of conceptual labor analysis is to produce models that are not in doubt. If the necessity of a component is a matter of debate, that debate should generate new questions or cause important realizations, producing better models or new working methods.

Step Three: Pick a model or go back to Step 1

Proposing new models and comparing them to existing ones is at the heart of conceptual labor analysis. It is a way to tweak the settings of your labor and imagine how it would behave if specific components were added, removed, or changed. Often the process can stop here, and we can return to more direct work with a better “sense” of what we are doing without going so far as to write it down in detail.

If a model we have confidence in produces instructions that we can reliably follow, our conceptual labor may be over and we can return to a conventional narrative. If it doesn’t, we have to repeat the process. How are we modeling our labor? What would happen if we changed that model? We ask these questions until we don’t have to.

To demonstrate how Conceptual Labor Analysis can describe our individual experience of labor, and how it allows us to identify the difference between conventional and conceptual labor, we need a narrative of labor. First we will go through it like a story, from start to finish. Then we will use Conceptual Labor Analysis to diagram the models that drive the story forward and to account for how the story changes.

Example: How to Do Conceptual Labor in the Woods

An adventurous friend draws you a map to a secret, picturesque picnic spot she discovered just the other week. In a nearby state park full of rocky hills, a small alpine lake, surrounded by verdant green fields and rare wildflowers, can be reached by a short hike from a public path.

The directions

Take the public path for a few kilometers from the trailhead until you see a large boulder on the right. Hidden behind it is an unofficial trail. Follow the trail uphill another kilometer or two until you hit the lake.

The Hike

The day of the hike arrives. With a full bottle of water, a blanket, a book, and a hearty lunch, you set out on the trail. You leave your phone behind to really unplug for the day.

After walking for some time, you spot a jagged boulder on the side of the path the size of a small car. You peer behind it to see, indeed, there is a rough path behind it. You leave the trail for the path, noticing that it’s perhaps a little rougher than you expected. But that’s just the kind of path your friend is always taking, and you remind yourself that the less trodden this path is the more peaceful your picnic will be.

After half an hour of grueling uphill scrambling, that story begins to wear thin. The “unofficial trail” disappears entirely at points, leaving you to fight the thick underbrush and push past saplings. Once the public trail was out of view, your path got much steeper – at points you had to hang on to branches as you climbed. How far is one or two kilometers, anyway?

The land finally begins to level out and the trail opens up into a clearing. Far from the oasis you were promised, patches of scrub cling to a small rocky plateau in the hillside with no lake to be seen. Was your friend playing a joke on you? Lakes don’t just dry up, do they? She was just there recently – you saw pictures!

You’re tired and confused, but at least you have lunch. Unsure of what else to do, you find a patch of scrub near the hillside, set out your blanket and unwrap your sandwich. As you eat, you review the directions. You followed each step, and there’s no way your friend would expect you to hike further than you did. You left behind “moderate hike” about 100 meters below. It’s not going to make your sandwich taste any better to keep thinking about it, so you try to get comfortable and enjoy your lunch.

That turns out to be difficult. There’s shards of rock everywhere – you clear some from under your blanket to get a better seat. Chewing your sandwich, forgetting about the trail for a moment, you look up to see that the break in the hillside you’re leaning against is a fairly fresh looking fissure in the bedrock. A clean face of stone five meters high sticks out from the hillside, some newly-exposed roots of trees creeping over the top edge like a woody hand.

That’s when you notice it – the rock is the same color as the boulder you saw at the path. Similar rocks dot the landscape all throughout the park, but the sense of familiarity you get looking at the fissure is impossible to ignore now that it’s struck you.

Roused by an idea, you leave the other half of your sandwich in your basket and walk to the edge of the plateau. The view is surprisingly good – you can see much of the valley below and even the public path. Beside it, some distance beyond where you turned off, a massive granite boulder stands, rounded with age. With that as your landmark, you follow the view off to the right until you see, sparkling in a valley about a fifty meters below you, a pristine small lake.

Suddenly, it all makes sense. The path you followed wasn’t made by humans – it was cut by the boulder you saw at the edge of the public trail after it tumbled from the very cliff where you had your lunch.

As is often the case, the trip back seems to go much faster than the trip there. On the way, you realize that many sections of what you told yourself was the path were just narrow passages between trees and bushes. Once you reach the public trail, you walk another ten minutes, past a few turns, and there it is – a massive boulder with a humble but well-established footpath sneaking around the side of it off into the woods.

As your friend promised, it weaves through the trees at a moderate incline until reaching a clearing. The lake is clearer than you imagined, the fields are a perfect green, and the wildflowers are in bloom. Luckily, you still have half a sandwich.

A Caveat

Before we attempt to articulate the doing of conceptual labor in terms of the Theory, we must recognize that this is an artificial and incomplete approach.

Dissecting labor to verbally label its component parts is an extreme option, likely to be far less efficient than the semi-instinctual, highly personalized ways that, as individuals, we model our labor in our heads and in the specific media of our disciplines. We must recognize that there is no inherent superiority to verbal or even rational analysis. We can gain deep, concrete insights into our conceptual labor from the body and its senses, the natural environment, embedded cultural knowledge, and even random chance. We will have a hard time listening to such sources if we expect them to only speak in words.

Conceptual Labor Analysis should not be used to submit the heuristic and often non-verbal strategies through which we do conceptual labor to the authority of rational description. In fact, by looking at labor closely, we should better recognize the complexity and value of efforts that may not always “look like work.”

Conceptual Labor Analysis shows how to verbally analyze your labor, most likely after you have done it, not “how to do conceptual labor.”

There can be no definitive guide to all forms of conceptual labor. It would certainly be an exciting and fruitful project to attempt to create a sort of pan-disciplinary pattern language,2 but that would be an enormous, multifaceted project, best attempted by a diverse team of experts. This book must be written first, as a framework in which to identify and discuss such patterns.

Becoming familiar enough with the Theory to wield it in your own way should be far more useful in most cases. That said, this particular method should still prove valuable in circumstances that are so complex or opaque as to demand that all those concerned take a collective step back to explicitly and methodically write down what they think they are doing in neutral, common language.

CLA of Our Example

Step 1: Define our project and model our labor

At the outset, this is quite simple. The project is to find the hidden picnic spot, and our labor is defined by the directions we’ve been given.

Project: Hike to the hidden picnic spot described in the directions

Actor: You

Work: Follow the directions

Context: The woods

We can create a conventional narrative from the project description by saying the Actor does the work in the context

Actorwork[proposition]context

Youfollow the directionsthroughthe woods

Step 2: Analyze and Compare Models

When things don’t go as planned, we don’t get much help from questions we frame within the conventional narrative.

- How far is one or two kilometers, anyway?

- Did we take a wrong turn?

Without GPS or some other way to expand our perspective on the problem, we don’t have helpful answers. So we have to question the narrative of our work itself:

- Was your friend playing a joke on you?

- Lakes don’t just dry up, do they?

In the absence of satisfactory answers, we go back to Step 1.

Step 1 Again: We need a model, not a narrative

When we give up and sit down to wrack our brains about what went wrong, we begin to consider the conventional narrative of our instructions in a number of possible broader contexts.

We must leave behind the “actor working in a context towards an end” structure entirely. Science-fiction author Ursula K. LeGuin vividly described the power of stories that exist beyond this paradigm in her 1986 essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.3

This theory is a rebuttal to these common assumptions about narratives:

…that the proper shape of the narrative is that of the arrow or spear, starting here and going straight there and THOK! hitting its mark (which drops dead); second, that the central concern of narrative, including the novel, is conflict; and third, that the story isn’t any good if [the hero] isn’t in it.

She proposes, instead:

…that the natural, proper, fitting shape of the novel might be that of a sack, a bag. A book holds words. Words hold things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.

One relationship among elements in the novel may well be that of conflict, but the reduction of narrative to conflict is absurd… Conflict, competition, stress, struggle, etc., within the narrative conceived as carrier bag/belly/box/house/medicine bundle, may be seen as necessary elements of a whole which itself cannot be characterized either as conflict or as harmony, since its purpose is neither resolution nor stasis but continuing process.

This image, of a container-story, is just the sort of thing we should have in mind when we work with models. Conceptual labor of all sorts, even step-by-step Conceptual Labor Analysis, will feel lighter if we accept that we are no longer telling a story that goes from start to finish with “me” as the hero, and instead try to find a suitable container for our experience, and discern what’s going on inside of it.

In Conceptual Labor Analysis, we build that container by turning our instructions into a model.

Earlier, we acknowledged that simply creating an ordered model with well-defined components is often enough to imagine a new, more effective approach when you are stuck. This is the first goal of CLA — to create a container-story that allows us to clearly see the defining qualities of what we’re doing, and how they relate to each other.

Contract workers or employees working for a “visionary” boss are likely to spend a surprising amount of their time on this step. When a mission or project is issued by someone who doesn’t have to be concerned with the “nuts and bolts” to someone who must be, the container-story is much like a carrier-bag, without internal order or a clear sense of scale, jumbling many things together.

The conceptual labor required to go from that to an orderly model with well-defined components is, a large part of the valuable work done by experts that is hard to see and understand from the outside4. Again, let us acknowledge that CLA is far from the only or best way to do that. The steps and methods here are, in a way, better for educational purposes than real-world application, as they allow us to proceed methodically and transparently through the process using the terms of the Theory.

The first step of CLA, then, is to define the project.

Model 1

Project: Hike to the secret lake

Then we list each fundamental component, and note which other components it can change, starting with the actors.

Model 1

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor | You | Self, W |

Project: Hike to the secret lake

When following reliable directions, you are the only significant actor. As a human being, you can alter your own state of mind in relevant ways by learning or deciding, and you can change the work you do or how you do it. However, at this point we labor under the assumption that we understand the context that matters to our work. We may not know everything about the parts of the park represented on the map, but we know we should not deviate from it, and that other contexts, like the other side of the park or our email inbox, do not apply to our project

Next, the work

Model 1

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor | You | Self, W |

| Work | Follow the directions | A |

Project: Hike to the secret lake

As mentioned previously, the work of hiking the trail has the potential to require conceptual labor as its own, more specific sub-project. But as long as we keep our footing, those situations remain closed-loops of conceptual labor, and do not need to be considered at this scale of modeling.

Otherwise, that work is literally legwork, in which case it can be considered a known quantity. A conventional narrative eschews work that is not included in its description, so our simple model, so far, does not include self-changing work. As the actor running the show, however, our state of mind and our behaviors would change with significantly different work — ie reading the signs of the trail vs scrambling up the side of a cliff. This means that work can change the actor.

Context

While we trust our instructions, our context is known and bounded. Remember, context is defined by what we believe to be true about the thing it refers to. We expect the park to be in a state that corresponds to the map and our expectations. However, not knowing everything about it, we would expect it to have the ability to change us, the Actor, even if it is just by greeting us with new sights. Through our reactions, work may change. So that leaves us with a model that looks like this:

Model 1

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor | You | Self, W |

| Work | Follow the directions | A |

| Context | The park | A, W |

Project: Hike to the secret lake

So far, there is little utility in analyzing this task to this degree. The project title sufficiently describes our work, and we can easily understand it in terms of the basic models of moving through the physical world that come with being a conscious person. This is conventional labor. This model represents the “let’s sit down and go over this one more time” point.

Step 2 again: Possible models

Unfortunately, this model doesn’t explain how we ended up on a barren plateau. When the reality of the path contradicts the expectations that our model is based on, we lose the one static and bounded component that shaped our labor — context. The context component is based on the expectation that things are where we think they are in the park. When that expectation is proven wrong, the meaningful context of our work becomes dynamic and intertwined with our state of mind as an actor and the actions we take. A bounded narrative no longer usefully describes our labor. As Tenet 2 states, our experience in the woods is now mediated by our model. We perceive our surroundings through the theory we hold about them, and we can redefine our experience by deciding that one thing is true and another is not.

Step Three: Pick a model or go back to Step 1

At this point, our labor can take so many different approaches that “steps” are no longer a relevant concept. We do the conceptual labor of making and interpreting models, and we do it until it resolves into a conventional narrative again.

The questions we asked while taking the first sandwich break propose a complex model that could explain our situation. Note that each type of component can change at least one instance of every type of component — the definition of conceptual labor.

Model 1

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You | Self, M1, W1, W2, C1, C2, C3 |

| Actor 2 | Your friend when she wrote the map | Self, W2, C1 |

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C2) | A1 |

| Work 2 | A1: Imagine what your friend (A2) was thinking (C3) | A1, W1, C1, C3 |

| Work 3 | A2: Make a map (C2) for A1 to follow | A2, C1, W1 |

| Context 1 | The map | A1, W1, C2 |

| Context 2 | The park | A1, W1, W2, C1 |

| Context 3 | Your Friend’s state of mind | Self, A1, A2, W1, W2, W3, W1 |

Project: Hike to the secret lake with unreliable directions

This model is rather general, and allows for many possibilities — you forgot a step in the directions, your friend is playing a joke on you, something in the woods changed, etc.

How to Read This Model

Written out, models must be read in a certain order, but the way we think of them is too complex to fit a certain sequence. So, when creating or reading a written model in Conceptual Labor Analysis, first concern yourself with understanding each fundamental component before turning to their relationships. A component description should be brief and capture the defining qualities of the component at the scale defined by the project titles. Components should be labeled as what type they are — actors, work, or context, and numbered accordingly when there are multiples of a type. The same applies to the project name and model name. Models should be numbered, as we will almost always be considering multiple models at once, and the project definition should be comprehensive but succinct, describing work at a single scale of specificity.

We label the model and project like so:

Model 1

Project: Hike to the secret lake with unreliable directions

And define components. Example:

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You |

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C2) |

| Context 1 | The map |

Project: Hike to the secret lake with unreliable directions

Components will necessarily have relationships. References to other components in a definition look like this:

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C2) |

This means Actor 1 does this Work that includes Context 2.

These are definitional relationships — relationships between components that are necessary to the existence of a component. In this case W1 cannot happen without A1 engaging with C2.

We label functional relationships in their own column, and we do so in a one-way relationship. If the current component has the capacity to affect the defining qualities of another component, we include that component in the third column of the model. We need not prove that the current component has affected another one. What matters is whether the actor who subscribes to this model believes that one component can affect another.

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You | Self, M1, W1, W2, C1, C2, C3 |

A component and its relationships

Let us annotate A1 as a demonstration of how to create and interpret a model.

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You |

Of course, this is an exceptionally short description for a very complex part of the model. This is a simple model for explanatory purposes, but your models don’t necessarily have to be much more complex at first. One of the major purposes of CLA is to discern significant details that are hidden by the way we define parts of the world to ourselves. More often, we have not taken the step to define a component explicitly, and only work with an opaque notion “you” rather than a detailed picture of a complex person.

As the primary actor, you have the most power to change the components of the model and the model itself (M1). The only component you can’t change is your friend in the past.

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You | Self, M1, W1, W2, C1, C2, C3 |

The components A1 (You) can affect.

These are the components that You have a functional relationship to.

Yourself

Conscious actors are self-modifying by definition. We learn, think, and decide.

M(odel) 1

Since Model 1 represents your own thoughts, you can change the structure of the model itself, not just individual components.

Work

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C2) |

The components A1 (You) can affect.

These are the components that You have a functional relationship to.

Yourself

Conscious actors are self-modifying by definition. We learn, think, and decide.

M(odel) 1

Since Model 1 represents your own thoughts, you can change the structure of the model itself, not just individual components.

Work

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Work 2 | A1: Imagine what your friend (A2) was thinking (C3) |

To change work is to change the meaning of its instructions. If you change what you believe about any of the contexts in which you are doing the work, you will change what it means to “follow the directions.” If you think your friend wrote the map with an ulterior motive, you may change the meaning of this work. If your friend is trying to trick you, which seems unlikely, then the directions must be interpreted rather than simply followed. You may articulate new directions to yourself, you may expand the definition of this work to include your own directions, you may discern subtext to C2 to navigate better, etc.

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Context 1 | The map |

This is even more fluid work, as it depends on your own imagination. Your capacity to change it is self-explanatory.

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Context 1 | The map |

As we do W1 and W2, our beliefs and knowledge about the map that our friend wrote may change. If we see something significant on our hike that the map doesn’t include, we will re-articulate the meaning of the map to ourselves, removing it from a position of authority to place it in dialogue with our observations as we move through C2.

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Context 2 | The park |

When we were following a conventional narrative through the park, the differences between reality and our expectations were only a reflection on our state of mind. The conceptual labor of hiking creates a dialogue between ourselves as Actors and our experience of the reality around us, which is represented here as C2. So we no longer treat the park as an external and static entity, we engage it as something dynamic that we relate to. C2 is what we believe about the park. Since an Actor’s belief is part of the definition of Context, it would be redundant to indicate that here.

| Label | Component |

|---|---|

| Context 3 | Your friend’s state of mind |

This is the context in which W2 takes place. By doing W2, you propose different definitions of C3.

That covers all the components that A1 can change. Since each component’s ability to change another is described in one-way relationships, we have not yet addressed the ways in which A1 can be changed by other components. At this point it should be clear that even a simple model like this contains a prohibitive number of possibilities to write out all at once.

Step 2 again: Possible Models

Exactly how much of any given model would be useful to explain in detail is a matter of judgement. We naturally think about models heuristically — that is we will only consider possibilities that we believe to be possible. More often we will only consider what we believe to be likely. When those beliefs change, our models must change.

For example, Model 1 would look very different if we thought our friend was a spy trying to lure us to our death, but our foundational beliefs about our friend and the state of the world at large make that possibility seem so unlikely that it is not included in our model.

Though this is an absurd possibility, it shows us that our Model is shaped by beliefs that exist outside of it — at the very least, our belief in what is possible or not. This concept is explored in greater detail in Tenets 5, 6, and 7 in the Expanded Theory, but for now we need to only consider that models have boundaries, and can therefor be contained by or contain other models. Our assumptions and limited attention can keep us from seeing, in detail, what’s going on in the models above, below, or next to the one we’re paying attention to.

Conceptual Labor Analysis helps us expand our scope of attention from the model we started with to the one that contains it. It helps us articulate the properties of different models, navigate their relationships, and discern what they really mean to our concerns.

A crucial part of the process is to come up with models that let us do this in a structured, internally-consistent way.

Model 1.1 Your friend’s intentions

The “My friend is a spy” model may be a dead end, but maybe she was playing a joke on you? That’s also unlikely, but not impossible. She could also have been mistaken, or distracted. We need a way to represent the possibilities that your friend, as a conscious actor, brings to the situation. Our description of her is as much of a placeholder as the word “you” is for your role, containing but not exposing many possibly relevant details.

Her state of mind, as you imagine it, (C3) is a very complex component — you would anticipate that she would anticipate you anticipating her. Hiking, while considering this, is very different work than just hiking. The work (W2) is more mental than it is physical, searching for a reason your friend would do something so obnoxious and of little benefit to her. Note that, in the example, we did a little bit of W2 in a closed loop to avoid changing our conventional narrative5. When the trail got rough, we imagined that our friend didn’t think that would be such a big deal for us. We thought about what she might think about us.

Once we begin trying to represent another person’s thoughts, we encounter the limitations of simple descriptions and “if-then” narratives. When we have to consider the inner workings of another conscious actor in any detail, we need a model to do so.

Since this is a hypothetical story, with a hypothetical friend, we won’t write out Model 2 — Your Friend’s State of Mind. We note it here to show how models can contain models, and how we often have to change the scope of our concerns in CLA from our initial model to models that are contained by it or should be considered in parallel with it.

Model 1.1

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You | Self, M1, W1, W2, C1, C2, C3 |

| Actor 2 | Your friend when she wrote the map | Self, W2, C1 |

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C2) | A1 |

| Work 2 | A1: Do CLA on Model 1.1 | A1, W1, C1, C3 |

| Context 1 | The map | A1, W1, C2 |

| Context 2 | The park | A1, W1, W2, C1 |

| Context 3 | Model 2 - Your friend | Self, A1, A2, W1, W2, W3, W1 |

Project: Hike to the secret lake with unreliable directions

The way we think about other people is a prime example of how we are able to think with models without making their every detail explicit. With those we know, we may possess a developed set of behaviors that closely resemble their real behavior that we can apply to questions of what they would or would not think and do. With those we don’t — or refuse to — know, we mentally represent them with what amounts to conceptual spare parts. The dangers of thinking of people as a collection of un-interrogated broad ideas, is demonstrated every day in every country.

However richly we choose to imagine our hypothetical friend, nothing in the story suggests that she was tricking you. We may quickly shunt parameters around our model of her state of mind, imagine their implications on Model 1, and reasonably conclude that this not a fruitful line of inquiry.

Another possibility

There is another complex component that is only represented in shorthand in Model 1 - C2: The park.

“Lakes don’t just dry up, do they?” is nearly as absurd a question as “Is my friend a spy?” but it implies a different state of M1 — one in which C2 lacks a satisfactory definition.

Model 1.2

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You | Self, M1, W1, W2, C1, C2, C3 |

| Actor 2 | Your friend when she wrote the map | Self, W2, C1 |

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C2) | A1 |

| Work 2 | A1: Imagine what your friend (A2) was thinking (C3) | A1, W1, C1, C3 |

| Work 3 | A2: Make a map (C2) for A1 to follow | A2, C1, W1 |

| Work 4 | Understand C2 | Self, M1, W1, W2, W3, C1, C2, C3 |

| Context 1 | The map | A1, W1, C2 |

| Context 2 | Model 3 - The park | A1, A2 W1, W2, C1, C3 |

| Context 3 | Model 2- Your friend’s state of mind | Self, A1, A2, W1, W2, W3, W1 |

Project: Hike to the secret lake with unreliable directions

While this is our working model, W4 is our preoccupying task. If we only imagine that the lake could have changed, we should refine our context to refer to the lake only rather than all of the woods. But, as it turns out, this more general model contains the possibility that explains our situation. The lake didn’t change, but the cliff did.

In our example, we arrived at that possibility by accident, as the contents of our model/container jostled against each other. Out of exhaustion, we took a break from what we thought was work and just looked ahead idly. When we understand the importance of creating and interpreting dynamic models, we can see why chance or accident can act just like work. This is why conceptual labor doesn’t always look like work, since sometimes the most useful thing you can do is to open your models to possibilities that seem unlikely under your working narrative. Any activity that helps you expand, articulate, navigate, or discern significant qualities of your models has the potential to yield the answers you seek or to refine the questions you ask.

However we arrived at our solution, it came from understanding the woods as more than the static context in our first model. If we go through even a cursory process of modeling it, we can see many ways in which we can consider it an actor, capable of complex work within our main model. Wind, rain, other hikers, plants and animals all have functional and definitional relationships to things that concern you and your labor, even if they are completely indifferent to your existence.

We must remember that our original model was reasonable. We were quite justified in thinking that the major features of a map made by an experienced hiker of a public park would be where we expected them to be. In fact, our solution does not contradict this. They were we expected them to be, we just saw things that weren’t on the map that a reasonable person could mistake for the map’s landmarks. We must do conceptual labor, whether we engage in CLA or other strategies, when good ideas and reasonable assumptions lead to bad results.

As is often the case, we arrived at a new, more accurate model in our example not by sitting down and writing it out, but by observing something that significantly expanded our original one. The work to write out a Model 1.3 that can fully describe the conceptual labor that solved our problem is an exercise left up to the reader. Perhaps it is a model that includes the work to read the map critically, or one that includes a more thorough model of the park and how it behaves. However we choose to model our labor, once we arrive at a sufficiently descriptive model, we throw it out.

This is the last important note from our example — that our best model allowed us to stop doing conceptual labor and return to hiking.

Modeling labor leads to simpler models that eventually become a direct narrative.

If the woods are the component that behaves unexpectedly, you can go back to trusting your friend and remove her state of mind from significant consideration.

Model 1.x

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You | Self, M1, W1, W2, C1, C2 |

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C1) | A1 |

| Work 2 | A1: Compare M3 to C1 | A1, W1, C1 |

| Work 3 | Understand C2 | Self, M1, W1, W2, W3, C1, C2 |

| Context 1 | The map | A1, W1, C2 |

| Context 2 | Model 3 - The park | A1, A2, W1, W2, C1 M3 |

Project: Hike to the spot your friend went to and remain aware of changes to the park

This is what Conceptual Labor Analysis should do for us — systematically navigate our models so that we can discern which component or model needs to be expanded or better-articulated.

We can simplify this model further

Model 1.x

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | You | Self, M1, W1, W2, C1, C2 |

| Work 1 | A1: Follow the directions on the map (C1) | A1 |

| Work 2 | A1: Pay close attention to the parts of the park that correspond to the map (C1) | A1, C1 |

| Context 1 | The map | A1 |

| Context 2 | Your observations of the park | A1 |

Project: Hike to the spot your friend went to and remain aware of changes to the park

Our work expects dynamic contexts, so context changes cannot loop back to change work. Our critical reading of C1 and our personalized definition of C2 can accommodate unexpected results from doing W1 and W2 without changing the definitions of our components. Put another way, we expect to learn as we hike. Any conceptual labor that happens in the process would do so in a closed-loop that does not challenge the structure of this high-level model.

With a little bit of W1 and W2, you can confidently settle back to a conventional narrative:

You follow the directions, paying close attention, through the woods.

Case Study: What is Programming?

The journey in our example may be straightforward, but many of us are more likely to find ourselves lost in a virtual wilderness, losing trust in our electronic maps — user interfaces. Even when they are designed to help us accomplish a certain goal, we often find ourselves laboring to understand them rather than use them6.

In his 2012 talk, Inventing on Principle, interface designer Brett Victor said something about programming computers that may resonate with readers who have felt this way.

In order to write code… you essentially have to play computer. You have to simulate in your head what each line of code would do on a computer. And to a large extent, the people that we consider to be skilled software engineers are just those people that are really good at playing computer. But if we’re writing our code, on a computer, why are we simulating what a computer would do in our head? Why doesn’t the computer just do it, and show us? 7

Of course, filling out a basic form isn’t the same as writing code. But if, as Victor says, “playing computer” is important, legitimate work to a coder, we can see that some of it sneaks into the conceptual labor we are forced to do to interact with a faulty interface8. With that in mind, we could create a high-level model that meaningfully describes both the labor of a coder or a frustrated computer user.

Model 1

Project: Make a computer do what you want

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 2 | The Computer | Self, A2, W1, W2, C2, C3 |

| Work 1 | Provide the correct instructions in the correct format | Self, A1, A2, W2, C1, C2 |

| Work 2 | (A1) Interpret the behavior of A2. | Self, A1, W1, C1, C2 |

| Work 3 | (A2) Interpret the input of A1 (W1) | Self, A1, A2, W1, W2, C1, C2 |

| Context 1 | What you think you’re doing | Self, A1, A2, W1, W2 |

| Context 2 | A1’s understanding of A2’s behavior and C3 | Self, A1, W1, W2, C1, C2 |

| Context 3 | A2’s interpretive conditions | A1, A2, W1, W2, C1, C2 |

Ideally, a computer user wouldn’t have to “play computer” as much as a coder, and this model would be much simpler for them. But, of course, coders are computer users too. The Theory reduces this confusion by allowing us to think of anyone doing labor described by this model as an actor, and worry about labels later.

So if we got to this model from using a faulty interface — or at least one that failed to meet the expectations we brought to it — then maybe it’s not the ideal model for an actor who has an idea that requires a computer to bring into the world.

This is the main thrust of Victor’s talk — that “creators need an immediate connection to what they’re making,” and that our current human-computer-interfaces stand in the way of that connection too much.

To that end, he showed the tedious steps required to animate something — in this case a falling leaf — in the once-popular animation software Flash. He had to define points on a path the leaf would take, while at the same time trying to imagine how Flash move the leaf between them. Then he’d play it back and repeat the process to refine it, but the results looked artificial.

The thing is, I kind of know what I want. I can even kind of form that with my hand. But Flash doesn’t know how to listen to my hand.

He then demonstrated the same task in his own animation tool. In his app, an animator could program the motion of elements by drawing it in real time on a tablet. Victor quickly drew a fluid path for the falling leaf. He even added a spontaneous loop-the-loop, pointing out that it never would have occurred to do so in the traditional interface.

What Victor does with his hand in this presentation might not look like what we call programming, but nothing in our model says what programming has to “look like”. If he were typing code, he’d still be using his brain and his hands to tell a computer what to do. With a device that “knows how to listen to his hand” his hand just gets to speak more clearly.

The talk also contained demos of programming a computer game, generating an image with code, and even writing a classic search algorithm — all though interfaces that Victor had created to show immediate feedback of the human actor’s work, removing much of the burden to “play computer.”

In Conceptual Labor Analysis terms, Victor has critically assessed the monolithic, conventional model of “programming” to propose that a large portion of it is unnecessary. In his model, the computer actor, the human programmer’s work to simulate the computer actor, and the context of the computer’s responses have all been either removed or significantly simplified.

Instead, human actors could employ to a much more familiar model — visual interaction. Victor’s tool makes something go up or down when we move a slider or push it across the screen with our fingers. For sighted persons, understanding that kind of work is such a fundamental kind of labor, hardwired into our brains, that we don’t need to model it at all.

Victor’s analysis of the conceptual labor of “programming” has expanded its definition, made it much easier to navigate, given humans a tool to articulate their ideas more clearly, and discerns a new qualities of what makes a good programmer. Much of his work since then has made material progress towards a new model of the labor of programming that does not include “playing computer.”

Educator Debbie Chachra did similar conceptual labor in her 2015 essay, Why I Am Not A Maker. In critiquing how tech culture valorizes “makers,” Chachra questioned how much of the popular conception of the labor of programming is defined by the framework of social values in which it is done.

She does not object to “making” itself or the pride that many people take in it, rather she criticizes how the the special status of Maker is given to coders and not other professions that produce intangible products.

Code is “making” because we’ve figured out how to package it up into discrete units and sell it, and because it is widely perceived to be done by men.

But you can also think about coding as eliciting a specific, desired set of behaviors from computing devices. It’s the Searle’s “Chinese room” take on the deeper, richer, messier, less reproducible, immeasurably more difficult version of this that we do with people—change their cognition, abilities, and behaviors. We call the latter “education,” and it’s mostly done by underpaid, undervalued women.9

Chachra’s reference to the Chinese room argument 10 evokes a high-level model which can plausibly apply to both coding and education, much in the same way that we proposed our first model to relate to Victor’s example. Searle’s argument imagines a Turing test administered by a Chinese speaker slipping notes under a door to an unseen party on the other side. As long as the mystery actor inside the room replied in fluent Mandarin, we would think they “knew” the language even if they were just following the instructions of a computer that could perfectly parse conversational Mandarin. Philosophical implications aside, Chachra’s use of this metaphor closely follows the process behind Conceptual Labor Analysis here by reconfiguring a model of labor in an effort to more deeply understand some of its components. In this case, she creates a shared context so that we may contrast the work and the actors.

Is that context usefully articulated? Teaching, of course, doesn’t have to happen in a classroom, so, yes, it could technically happen by way of notes passed under a door11. Maybe that would be a very slow way to learn, but if education has a minimum speed then a lot of what happens at schools wouldn’t count. How about programming?

Victor’s work has already produced strong examples of how to program without touching a digital computer12, but we can find a mainstream example in the tech-world convention of the whiteboard interview. In it, interviewees are often challenged to demonstrate how they would solve a computer science problem — in relevant detail — on a whiteboard. Whether or not this is an effective interview practice, its popularity demonstrates a practical acceptance of the idea that the conceptual labor of programming can be meaningfully done, at least in part, with a pen.

So we can imagine a programmer and an educator, standing side by side in front of an ornate door, each slipping notes inside to ply their trade. Chachra has already defined the fundamental work that they each must do for the mysterious actor behind the door: “change their cognition, abilities, and behaviors.” The written model of this labor would similar enough to M1 that the Conceptual Labor Analysis to write it out is another exercise for willing readers.

Being able to imagine such a model means we can compare it to other models or reconfigure it to articulate specific definitions of labor — in this case “making.” This is exactly what Chachra does — she asks what difference it makes to do this work with people rather than computers, whether the actor is a man or a woman, and whether or not the work creates a fungible product. Having done this Conceptual Labor Analysis on her own terms she concludes:

I am not a maker. In a framing and value system that is about creating artifacts, specifically ones you can sell, I am a less valuable human. As an educator, the work I do is superficially the same, year on year. That’s because all of the actual change, the actual effects, are at the interface between me as an educator, my students, and the learning experiences I design for them.13

Here, too, she carefully articulates the context of education to discern a narrative that hides the actual product of her labor — educated humans. It’s not that the work the programmer does by passing notes under the door turns into something and the work of the educator goes into a black hole. It’s just that the work that happens in the context of a human mind is “deeper, richer, messier, less reproducible, immeasurably more difficult.” Certainly, it’s worth the effort to learn to see such labor clearly.

-

We can find an example of this in the programming term “Rubber duck debugging.” This is a method in which programmers describe their code, step by step, to a rubber duck (or other inanimate object) on their desk. Since the duck can’t respond, they are forced to describe and consider, from square one, every assumption and conclusion of their code. Originally coined in Hunt, Andrew, and David Thomas. The Pragmatic Programmer from Journeyman to Master. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 2000. ↩︎

-

See also Alexander, Christopher, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977. ↩︎

-

Le Guin, Ursula K, and Donna Jeanne Haraway. Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 2020. ↩︎

-

Surveyed in the previous section, We Are Always Writing Theories of Conceptual Labor. ↩︎

-

This is a hypothetical demonstration of Tenet 4. ↩︎

-

Another example of Helping / Not Helpful. ↩︎

-

Victor, Bret. “Bret Victor, Beast of Burden.” Accessed May 8, 2021. http://worrydream.com/#!/InventingOnPrinciple. ↩︎

-

Here is an example of a professional application of CLA. User experience designers could model computer users’ labor that, superficially, appear to be an end-user interacting with a finished product. The more the model resembles models of software development, where a user must “play computer” to achieve a straightforward goal, the less the helpful the interface is. This position is encapsulated in the design term The Principle of Least Astonishment. “Principle of Least Astonishment.” In Wikipedia, March 13, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Principle_of_least_astonishment&oldid=1011856538. ↩︎

-

Chachra, Debbie. 2015. “Why I Am Not a Maker.” The Atlantic. January 23, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/01/why-i-am-not-a-maker/384767/. ↩︎

-

Cole, David. “The Chinese Room Argument.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2020. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/chinese-room/. ↩︎

-

And, in fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced educators, parents, and students to re-consider the essential components of their model of education, and whether it can be achieved remotely, though a narrow interface. ↩︎

-

VVictor’s recent project, Dynamicland, was a space in Oakland, California where California where visitors can program computers with pen and paper within a system of cameras and projectors that run their programs in real time. ↩︎

-

Chachra, “Why I Am Not a Maker.” ↩︎