Why We Need a Theory of Conceptual Labor

- Maps Are Not Always Perfect

- Doing the Wrong Work Well Still Doesn’t Work

- Expertise Grows out of Conceptual Labor

- How We Talk About Work and Labor Reveals What We Value

- We Are Always Writing Theories of Conceptual Labor

- The Art of ___, Diagrammed

- Conceptual Labor Counters Power

Maps Are Not Always Perfect

We know how to follow a complete, accurate map — it is mainly conventional labor. We may still face a challenging journey moving through unfamiliar territory, but the obstacles lie within known boundaries — to get from point A to point B, that river needs to be forded, that hill must be climbed, etc.

It is very different work if the map is wrong. When faced with an inaccurate map, filled with unseen errors, we must do conceptual labor. Even the most skilled explorer cannot predict that the trail ahead will be blocked by a landslide if they are the first traveler to encounter it.

Of course, if our traveler knows the land so well, they could discover, through their observant bushwhacking, that they cannot trust the map. The moment they realize this, their labor takes on a new dimension. The map must enter into a dialogue with the changing conditions of the journey, to be updated as our adventurer deepens their understanding of the landscape. Before, their labor proceeded as they did — as directly as possible from their starting point to their destination. But when they turned back to re-consider their route, their labor became a cycle too.

The land an explorer moves through is incontrovertibly real, but with or without a map they travel primarily through their own hypothesis of the land. They stay on path only as much as their conception of the land aligns with the earthly facts around them. When the landscape rebukes their expectations, they must proceed in cycles through perception, experiment, and re-conception. The conventional labor of hiking along a known path is still necessary, but it is no longer the sole task. It becomes a proposition rather than a description, and must be observed as athletically as is done.

Doing the Wrong Work Well Still Doesn’t Work

A bad map will still get you lost no matter how carefully you follow it. A type of folktale to this point has circulated for hundreds of years, one of the earliest examples being a classic misadventure of Mulla Nasreddin:

Mulla had lost his ring in the living room. He searched for it for a while, but since he could not find it, he went out into the yard and began to look there. His wife, who saw what he was doing, asked: “Mulla, you lost your ring in the room, why are you looking for it in the yard?”

Mulla stroked his beard and said: “The room is too dark and I can’t see very well. I came out to the courtyard to look for my ring because there is much more light out here.”1

Everyone has done work which felt productive at the time only to discover that it had actually accomplished nothing. The illusion of productivity came from following a narrative about how to work well, not from meeting the actual requirements of the task. (Having good light where you’re looking isn’t a bad idea, after all.) When this happens, it is easy to believe that we had the wrong instructions, and the right ones are out there somewhere. If we could just find them, we’d be able to follow them faithfully to the solution.

It is much harder to consider that some work has no straightforward story — that it must be done in the dark. Some work can only be understood as one does it, some work continuously changes so it will never be fully described, and some work must be invented as it occurs. Such work frequently involves other people, learning something new, or understanding the behavior of a complex system. When we attempt to apply conventional narratives to this kind of work, we create new problems and fail at our original task.

Expertise Grows out of Conceptual Labor

One of the most important circumstances where conventional labor falls short is when there is no map in the first place. It is through conceptual labor that we create new ideas, shift paradigms, and learn.

In his explanation of the difference between advanced degrees, computer science professor Matt Might provides a clear, charming way to picture the difference between working within a frame of reference and working on the frame itself. In The Illustrated Guide to the PhD2 , Might pictures all of human knowledge as a circle. Primary education fills a smaller circle at the center. Bachelors and masters degrees extend a specialty like a spoke from the center, and professional research brings you to the “edge of human knowledge.”

, a professor in [Computer Science](http://www.cs.utah.edu/) at the [University of Utah](http://www.utah.edu/), created [The Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D.](http://matt.might.net/articles/phd-school-in-pictures/) to explain what a Ph.D. is to new and aspiring graduate students.](images/illustrated-phd.png)

See Figure 1 next page

Note that not only do the different stages of learning take distinct shapes, but work that expands the frame is accompanied by a profound shift in perspective.

We cannot understand expertise without talking about conceptual labor.

The unique value of the work done by experts comes from their ability to navigate, understand, and describe this kind of work, let alone execute it.

Painter James McNeil Whistler became famous not just for his portrait of his mother, but also for a statement on the nature of the conceptual labor of painting. Though quite influential on the development of modern painting, his work was once ridiculed for its simplicity by more conservative critics. One such review led to a famous libel trial, where he defied the idea that the value of a painting was tied to the time spent painting it. When pressed if he asked market prices for “the labour of two days”, he responded: “No, I ask it for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime.”3

A much more recent anecdote from economist Dan Ariely4 shows that the difficulty of putting a price on experiential wisdom isn’t just a problem for professional artists. He spoke to a locksmith who lamented that he lost wages as he gained mastery. When the locksmith was still a novice, he would struggle with locks for hours at a time, sometimes breaking them. His customers waited and watched the whole process, and tipped him well for all of his hard work, even if they had to replace their lock. Once he became an expert, however, he could open locks in a fraction of the time, with apparent ease and without damaging them. Not only did this cause his customers to tip him less, but they started complaining about his base fee, even though they were getting a more valuable service. This locksmith had encountered his profession’s version of a refrain that painters have been hearing since at least Whistler’s time: “Well I could do that.”

Conceiving of Work is Work

The point here is that simply knowing what to do can be deceptively difficult. Conceiving of work is work5.

When we encounter work that lies beyond our imagination, we still judge it within the limits of our current understanding. Novices only see the work once it has been conceived, and without the domain knowledge, experience, and judgement of an expert, they fail to see how the work must be continuously re-conceived as it is performed. They don’t appreciate the work it took to produce what’s in front of them at any given moment because, in part, they can’t see it without doing at least some of the work itself6. Conceptual labor creates the very ground on which it is performed.

The Endless Argument

We have all been confronted by a complex task that, when prepared and executed by an expert, looks like child’s play. Yet everyone is an expert in something, even if it is only where to find things in their kitchen. At some point we have all struggled to explain, to ourselves or to others, why the real, tricky thing we are trying to accomplish is much more complex than it appears from the outside. We have no guarantee that the conceptual labor we have done to make our expert work possible will be visible to observers, and it is difficult to remember how a novice sees the task. To paraphrase Burton Rascoe,7 the spouses of writers will never understand that they are hard at work when staring out the window.

We have all been the writer, and we have all been the spouse, (or the locksmith or the customer, or the critic or the painter). Often we are both during the same project. As we produce and examine narratives of our own work, we are trying to see more than we can see. We will never fully appreciate the work we are trying to invent before we have invented it.

It is useful to recall the root of the word “expert” and forget its authoritative connotations; it reminds us that experience is a special kind of knowledge. Seeing the narrative of work for what it is rather than what we imagine it to be is the true difference between expert and novice. Novices may think experts work beyond the boundary of confusing work, where all the work makes sense to those that know enough about it. The expert, however, knows that they will continually lose sight of the work as it evolves, and they cultivate the skills and attitudes that let them freely move back and forth across that boundary of understanding.

The disagreement between an objecting, impatient novice and an expert trying to explain the transformative nature of their work plays out in our own heads as we do difficult, conceptual labor that continuously pushes us into new territory. Conventional narratives of work and the strategies that go with them assume that this disagreement will be an argument, and emphasize determination, persistence, and confidence in foreknowledge. These are fine qualities in the abstract, but also how you break a lock. A general theory of conceptual labor should provide rules of order to this argument so that it can become a lively conversation, full of productive debate and transformative surprises.

How We Talk About Work and Labor Reveals What We Value

Argument or revelation, this dialogue is shaped by our worldview, and the biases and ethics that come with it. What we consider to be work reflects our values.

If a brilliant scientist struggles and fails all day to solve a problem, takes a defeated nap, and then wakes up with the solution in mind, was the nap work? Was the struggle?

If we count that nap as work without extending the dignity to all naps, we can begin to expose a deep problem in the way that we talk about work. Would that nap, pregnant with insight, still appear worthwhile if it occurred at the end of the day — or after a week of fruitless work? Did any work actually take place during the nap, or did the scientist simply look at the problem differently after the nap? If so, does that mean looking is work? Photographers would say it is.

By convention, work is what we do that is not a waste of time. To be worthwhile is for our efforts have value justifying the time spent. The problem is, of course, that our notions of value are themselves contingent, biased, and subjective. It is not always clear how much of our time was “productive” and how much was “wasted.” To the locksmith’s customers, struggling with a lock looked more like work than delicately finessing it open.

The importance of hindsight exposes the uncomfortable fact that when we understand the value of our work has an enormous influence over the planning and doing of work. Hindsight may show us the full process of work, but even then we are liable to discount certain activities or thoughts if they don’t fit our existing notions of worth. A select few offices are willing to schedule naps into the workday when needed, but they remain outliers.

The conventional narrative of work cuts the worthy work away from the rest of the experience like a butcher slicing a cut of meat from the connective tissues that once held the muscle in place. How might we talk about the whole, live animal of work, without reducing it to “useful” parts, as it roams under its own power?

To do so, we have to regard the worker’s internal sense and narrative of their effort before any external measure of its results. When we say that caring for an ailing loved one is “hard work,” we come closer to the meaning of the term than anything having to do with commutes, offices, or paychecks. It is work because we do it, not because it produces value, follows instructions, or “looks like work”.

Mothers don’t go into work, they go into labor.

To talk about conceptual labor is to talk about behavior that we do not automatically or officially recognize as work. Of course, the danger in calling parts of our internal lives “work” is that we might start to expect them to reliably produce economic rather than experiential value. Common usage of the word “labor,” however, points in the other direction — that some of our behaviors are worthy just in the doing.

“Labor” and “work” are roughly synonymous when we define them by the doing of challenging, intentional activities, but there is a useful, though inconsistent, distinction in how they are used in practice in conversational English. “Work” tends to be what we say when we talk about this activity within the structure of employment — jobs, the people and institutions that seek them, do them, give them and take them away. We tend to use “labor” when we need to talk about the larger frame in which we experience work.

“Labor” is often what we say when we talk about about this whole system of work in a social context — if we dispute the the terms under which people may go to to work, we have a labor dispute. Taking care of another person is only work if we are paid to do it, or if we would rather not do it — otherwise it is a labor of love. What similar distinction can we draw between the implication of referring to a group of people doing something as laborers rather than workers? A prison worker is probably a non-incarcerated person working for the prison itself. Yet prison labor, a term nearly a euphemism for slavery, is done by the inmates. Labor, it seems, is something we must live with.

The Theory makes this distinction between these terms explicit — work refers to action taken within the full experience of labor.

What Other Kinds of Labor Theories Tell Us about Work and Value

The central proposition of the Labor Theory of Value8 is that the exchange value of anything should be directly tied to the amount of labor that went into producing it. We don’t have to debate Marxist theory to recognize that, despite its appealing logic, this is still an alternative economic system, and not the existing, financialized global economy in which we pay rent and short stocks. At the very least, it shows the many ways in which an economic measure of one’s labor will leave out many qualities of the experience of work that are important to the individuals doing it. Whistler’s trial, after all, hinged on the difficulty of measuring the actual work represented by a single painting.

The term “knowledge work9” also reinforces the separation between “work” and an individual’s full experience of it. It recognizes that “non-routine” work is increasingly necessary in a workplace where employees are expected to “produce” new “knowledge,” manipulate symbols, come up with new ideas, etc. Depictions of Knowledge Work can verge on what one might expect to see in a montage in a movie about a genius. It is still wholly oriented towards the workplace, and relates discussion of “non-work” strategies like our scientist’s nap to the requirements of employed work. Its overriding concern with managing the manifestation of conceptual labor in a workplace ultimately reinforces a definition of work by its outcome and external qualities. It does not tell us why fundamentally different strategies of knowledge work might arise under the same roof, applied to the same materials, nor how to organize and interpret those fundamental distinctions that can be reliably used by the knowledge workers themselves. In his essay “The Planning of Science,” Lewis Thomas summarizes this discrepancy in the knowledge work within the medical sciences:

We may as well face up to it: there is a highly visible difference between the pace of basic science and the application of new knowledge to human problems. It needs explaining.10

As a term meant to assist such an explaining, “conceptual labor” owes a debt to Arlie Hochschild’s term emotional labor.

In The Managed Heart,11 Hochschild studied the performative emotions required by the jobs of bank tellers and bill collectors. Coining “emotional labor,” she named a crucial, required component of many jobs that lay in plain view yet remained systemically overlooked because it did not fit into the conventional narrative of what constitutes valuable work. To name “emotional labor” is to recognize that the hidden nature of work extends to the social conditions of the workers themselves.

Many readers may have first encountered this term in the popular usage it has since acquired. Its non-academic definition is closer to “effortful emotional processing required in social circumstances by etiquette or the expectations of others,” such as the work behind composing a text message so that it will be well-received by the recipient. Hochschild has gone on record12 to argue for the importance of the term’s original context within paid work — that it exposes the otherwise tacit expectation that employees use their emotional, personal selves in a professional capacity.

In naming emotional labor, Hochschild looked at all the activities that were required of individuals working within a defined profession, whether or not those activities were included in that definition. This is what we must do whenever we are doing conceptual labor — critically assess our consciously held idea of work and change it to better reflect our experience and observed reality. If we drew one of Professor Might’s circles around what we call work, Hochschild put such a dent in it that the entire circle got bigger.

It makes sense that individuals would use this term whenever they feel like they are doing work, whether or not it is paid. Hochschild’s original use of the term distinguishes work from labor. The Real Work of being a bank teller excludes the personal conditions of the worker, such as their genuine emotions, but the teller’s full experience of their job — that is their labor — demands those parts of their experience. In social circumstances, we are still asked to do work with fixed definitions that don’t line up with our experience of doing it. “Just answer the question” is a sentence that defines its own parameters of Real Work, deliberately excluding all the other effort it might take someone to speak the answer — effort that could easily fit the popular definition of “emotional labor” if the question is a fraught one. So, while the popular usage can be problematic13 at times, it is consistent with the Theory that actors would argue, in any circumstance that requires effort from them, that what they are actually doing is different from what it looks like they are doing or what they are supposed to be doing, and that the effort has intrinsic value.

Our napping scientist reminds us that just because something doesn’t look like work doesn’t mean it’s not. Naps, by nature, do not create products. They are, however, valuable to individuals, and individual naps have certainly been vital, through contingent circumstance, to the creation of many valuable things. It is only within the conventional narrative of labor, in which we judge work by available knowledge and prioritize direct results, that a nap can never be work.

When we equate work with economic value we forget that it is also part of our behavior — our labor. If we are to describe the entire picture of our labor, full of learning, experiencing, and feeling, we must make a radical departure from the conventional narrative surrounding work.

We Are Always Writing Theories of Conceptual Labor

Over and over, experts beseech us to reimagine their labor in this way. From psychology to education to martial arts to mathematics, initiates of countless fields frequently advocate for alternative theories of labor from their perspective at the edge of Professor Might’s circle of knowledge. Though they address their profession’s concerns in the specific language of their field, most direct the reader towards deeper lessons that reflect both their training and their values.

We can find plenty of examples of this genre by looking for titles that start with “The Art of.14” “Art,” of course, is a loaded, imprecise term, but unpacking its uses by non-artists can provide insight into the dialog about doing conceptual labor that already exists.

In The Art of Computer Programming,15 when Donald Knuth appeals to the “aesthetic experience” of programming, he can do so from a distance that arts professionals must cross. In The Creative Habit16, choreographer and dancer Twyla Tharp cannot cover new ground by urging her readers to think of dance as an art. Instead, she compares art methods laterally, invoking design and sculpture. The challenge faced by practicing artists to explain how they do what they do reminds us that we lack a general vocabulary with which to navigate these shifting landscapes of methodology.

When considering all the many attempts to describe how to do the art of something that is not already called art, we should not ignore James Elkins’s classic study of art education, Why Art Cannot Be Taught.17

In the section, If Art Cannot Be Taught, What Can be Taught?, Elkins presents a list of four categories of subjects, skills, and resources that could be taught as part of a formalized art education. His brief summary ends without a solid answer.

Each of these four answers to the question of what art classes teach is partly right, but none is a good definitions of what happens in college-level art instruction… The problem with saying that art classes instill visual acuity or technique is that teachers and students do not behave as if those were their principal goals… Teaching at the graduate level is directed towards complicated questions of expression, control, self-knowledge, and meaning — subjects that have little to do with technique or sensitivity or even visual theory, and everything to do with the reasons we value art.

I am not denying that art classes can teach these four things, nor am I saying that they aren’t reasonable goals. But their marginal positions reveal how deeply we must believe that we are doing something else, whether or not we can say what it is. The other goal is nebulous, and it has to remain that way: otherwise teachers and students would be impelled to think about the contradiction between their claim that we can’t teach art, and the reality that we behave as if we might be trying to do just that.

Elkins sees the classical philosophical roots of the modern concept of art as a root cause of this “conundrum”. The Greeks distinguished between techne (technique) and emperia, the subjects that Aristotle said couldn’t be taught, only “absorbed, or learned by example18.”

What we think of as art is more like empeiria: it does not depend on rules so much as on nonverbal learning, things that can’t be put into words.

When reading treatises on the “The Art of ___”, if we factor out references to artiness — the implication that there is something inherently elevated about art making — we are usually left with a discussion of the empeiria of their subject. They present evidence of valuable processes and concepts that cannot be directly learned or even inferred by beginners from the available curricula. Recognizing that this material can’t simply be explained, they combine specific domain knowledge with various indirect strategies meant to cultivate insight in the readers.

In general, you can find this material presented as:

- a distinct way of working that remains aware of the big picture

- a general guide rather than a specific route to follow

- meriting consideration in areas outside of the field, sometimes in all types of work or “life in general”

- a way of working that includes consideration for the individual doing the work

- indications of a deeper pattern to the work described, sometimes one that resists complete explanation.

The Lost Art of Reading Nature’s Signs employs most of these approaches when describing its particular art:

Most guidebooks for walkers give the reader information about a particular location. This one does not; instead it lays out techniques that can be applied on any walk in almost any area, and demonstrates how these techniques can be combined to make the walk more interesting than the sum of its parts19.

The art its title refers to is not just the skill of identifying different plants and animals, it is “the art of making predictions and deduction.”

The Art of something is a way — a process. So, while our bulleted list may be a handy start, we find that its qualities must be discussed in an integrated way. Talking about one leads us to another. This is the effect of presenting “a distinct way of working that remains aware of the big picture.”

We don’t need a precise definition of whatever “art” refers to in these cases to realize that experts of all types propose alternate maps based on their experience, and that they often point in the same direction when doing so. Perhaps the routes on these maps remain evasive because they concern evasive qualities, and perhaps they are constantly being redrawn because they concern change and conceptual progression. Perhaps we keep publishing treatises on the art of this hard topic or the science of that squishy topic because there exists a parallel episteme that asks and answers questions using tools from both the artistic and scientific traditions without regard to the boundaries of disciplines.

These methods don’t simply contradict conventional wisdom. Rather, they diverge or overlap with available knowledge according to an exhaustively argued methodology that addresses fundamental concerns at all levels. They attempt to present a systemic understanding of the material, and in doing so must acknowledge that their topic is often taught mainly by focusing instead on what can be explained or tested.

Often the first map that we are given is one that sticks to paved roads, and there are many careers in which you can make tremendous progress by developing a well-outfitted off-road vehicle. But if we are to truly know the territory, we must also hike by foot, listen to the flora and fauna, sometimes swim, or even go up in a hot-air balloon.

No map will prepare a novice for every territory, or even every eventuality in their chosen field. However, across disciplines we see experts lead with advice about how to critique available maps and draw your own according to fundamental principles about the material and the labor it takes to engage it.

In The Art of Doing Science and Engineering,20 engineer Richard Hamming also draws on a classical distinction between the teachable and empeiria, urging his science-minded students to appreciate the importance of style in their work. Rather than just teaching them science knowledge, he aspires to provide a “meta-education” that will guide a lifelong career. Chris Argyris’s Teaching Smart People How To Learn21 makes a similar case in the language of corporate management.

Educator William Ayers directly engages this tricky process of learning and teaching in To Teach. He begins with a list of myths perpetuated by education degree programs, reorienting their concerns to the full context of real-world classrooms. He defines teaching as the “vocation of vocations, because choosing to teach is to choose to enable the choices of others.”22 This kind of teaching is a way of engaging individual students, not a program of transmitting information. Writer Zadie Smith’s concerns about the pervasive importance of style in her work leads her to describe writing as the “craft that defies craftsmanship” in her essay, Fail Better.23 A writer’s style is their “manner of being in the world.”

When you understand style in these terms, you don’t think of it as merely a matter of fanciful syntax, or as the flamboyant icing atop a plain literary cake, nor as the uncontrollable result of some mysterious velocity coiled within language itself. Rather, you see style as a personal necessity, as the only possible expression of a particular human consciousness. Style is a writer’s way of telling the truth. Literary success or failure, by this measure, depends not only on the refinement of words on a page, but in the refinement of a consciousness, what Aristotle called the education of the emotions.

The appeal to style is a practical consideration of how to develop rote skill into method. When experts make a map-of-maps, they know you will not just read the maps it contains, but situate it among other maps and maps-of-maps. So they present a style — a methodology that can be coherently abstracted and applied to unknown contexts. Mathematician Eugenia Chang, author of The Art of Logic,24 considers the abstractness of category theory to be one of its most important qualities, which “means that we can apply it much more broadly to the whole of life in ways that might be surprising.” Technologist Brett Victor’s talk Designing On Principle25 makes a similar appeal to coders and designers, that the abstract methodology behind their specific work should have integrity with the broader social context that frames it.

Simple Instructions, Hard to Follow

Of course, the problem indicated by the recurring appeals to something like emperia is the impossibility of fully abstracting style. The instructions are simple while the doing is not. This problem has garnered its own, continuously-re-attributed anecdote: someone asks a sculptor, maybe Michelangelo, if their work is hard. The sculptor says no, all you have to do is remove all the marble that isn’t part of the sculpture.

The deceptively simple instructions for doing conceptual labor have been annotated, expanded, and encoded in the literature and practices of countless disciplines. Many robust and well-researched conceptual frameworks exist to consciously steward the expected conceptual labor of their adherents. These include, but certainly are not limited to, studio practice, critical theory, pedagogy, andragogy, job crafting and non-canonical work, agile methodology, improvisation theory, metacognition, social framing theory, and design thinking. If experts create maps-of-maps, such frameworks are like libraries of maps. This metaphor suits the fact that experts in so many different fields say many of the same things about the “art” of their work. Dig deep enough in one section of a library and you’re likely to find yourself in subject you previously thought unrelated. How to use a library is also its own skill to develop, whatever you’re looking for.

The Theory does not mean to replace or unseat any of these existing frameworks. Rather it aims to provide a mental cataloging system, useful in libraries familiar or strange.

We need such a theory, because every field’s own Pricipia Mathematica26 can be met by a matching ad-hoc incompleteness theorem.27 However successful our work to order and rationalize the world may be within its goals, our actions and their results become a part of the world that we encounter and must relate to our other labor as conscious actors. We situate these frameworks along chronological, conceptual, personal, or completely novel measures. Whatever frame we may build in which to work, it is our nature as frame-builders that allows us to always step out of one frame and consider it in a broader context.

In his essay The Role of Theory in Aesthetics, Philosopher Morris Weitz attends to the problem of defining “Art” when new theories and new art continue to develop.

Because work N + 1 (the brand new work) is like A, B, C … N in certain respects … the concept is extended and a new phase of the novel engendered. “Is N+1 a novel?,” then, is no factual, but rather a decision problem, where the verdict turns on whether or not we enlarge our set of conditions for applying the concept. What is true of the novel is, I think, true of every sub-concept of art: “tragedy,” “comedy,” “painting,” “opera,” etc. of “art” itself28.

In seeking a consistent, general theory of aesthetics, Weitz’s work has to follow this same pattern, which, he says, is the pattern of an artist making art. He considers all the theories that comprise the frame in which he works, and seeks a theory that can continually create — and then escape — new, expanded contexts. The subject of his Art of ___ happens to be “art,” but that doesn’t make it special. As we have seen, it is the pattern of work, not the subject, that matters. The art of figuring out the art of art seems to be the same thing as whatever “art” is.

Half a century later, Weitz’s theories contributed significantly to Nigel Warburton’s The Art Question29, a sort of guide to asking “what is art?” Proceeding from Weitz’s position that it was “a logical mistake to look for the essence of art,” Warburton developed his hypothesis “that ‘art’ is indefinable on the grounds that this is the most plausible position given the evidence.” His conclusion, which he calls “even more tentative” than Weitz’s:

Those philosophers seeking a watertight yet general answer to the question “What is art?” should be left to their own devices. For most of us, the rewarding questions in this area will be the questions that touch real works of art. This is nothing to be embarrassed about. The whole point of the art question is that it is asked by people interested in works of art, not simply in the idea of art. Ultimately, we must turn back to the works themselves.

Like the artists Weitz imagines, and like Weitz himself, the viewer does not get a guidebook to art. They must look, consider the context, consider the new thing and its new context, and look again next time. All these treatises on the “art of” a topic ultimately concern themselves with this process — how to work attentively within a specific and declared set of rules and ideas, while continuously relating to contexts outside that set. These may be big, encompassing concepts (like “art”), parallel disciplines, or hazy yet compelling personal experiences. For whatever work you do here, there is the unknown work out there that reveals itself to a curious mind at work.

The work we do to step out of a frame is different than the work that stays only within the frame because it is unbounded. It is what philosopher James P Carse calls an infinite game.

Infinite players cannot say when their game began, nor do they care. They do not care for the reason that their game is not bounded by time. Indeed, the only purpose of the game is to prevent it from coming to an end, to keep everyone in play.30

There are no spatial or numerical boundaries to an infinite game. No world is marked with the barriers of infinite play, and there is no question of eligibility since anyone who wishes may play an infinite game.

Generally, Art of __ texts can be read as a way of relating the finite games of the author’s discipline to the infinite game of their pursuit and experience of that discipline.

Finite games can be played within an infinite game, but an infinite game cannot be played within a finite game. Infinite players regard their wins and losses in whatever finite games they play as but moments in continuing play.

However, as readers of these texts, we are in the same situation as a viewer in front of a painting — looking for the concept of an art in the practical expression of it. The work we do cycles back and forth between bounded and unbounded contexts, open and closed concepts, finite and infinite games.

This work is the +1 in N+1. There can be no one guide to it, so we write countless guides. One particularly profound and surprising entry is Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost. In it, she meditates on a challenge posed by Meno to Socrates: “How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you31?” Whether we answer that we will do “conceptual labor” or use another term, we must at least recognize that the answer falls within a special category of labor, one which is always changing.

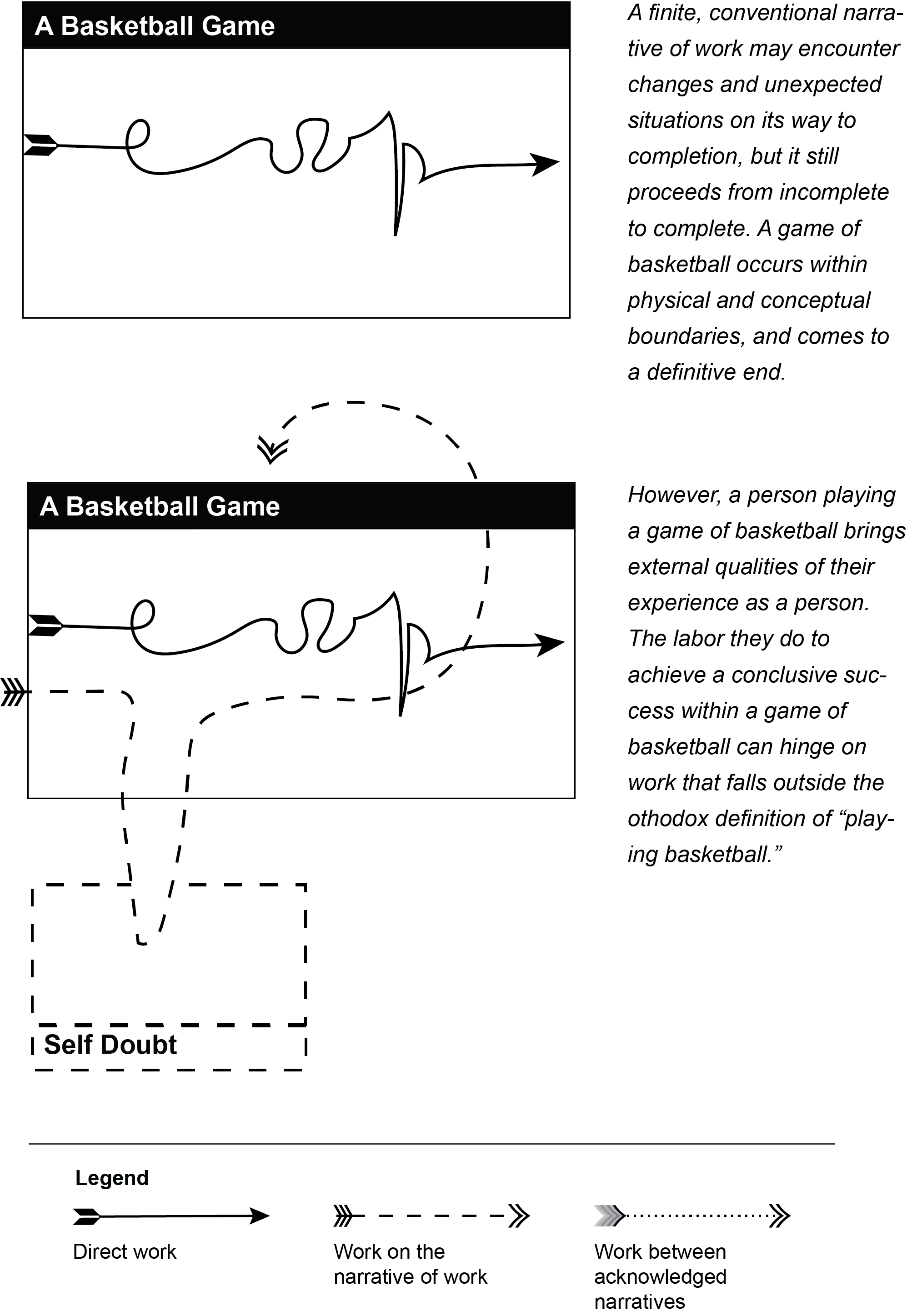

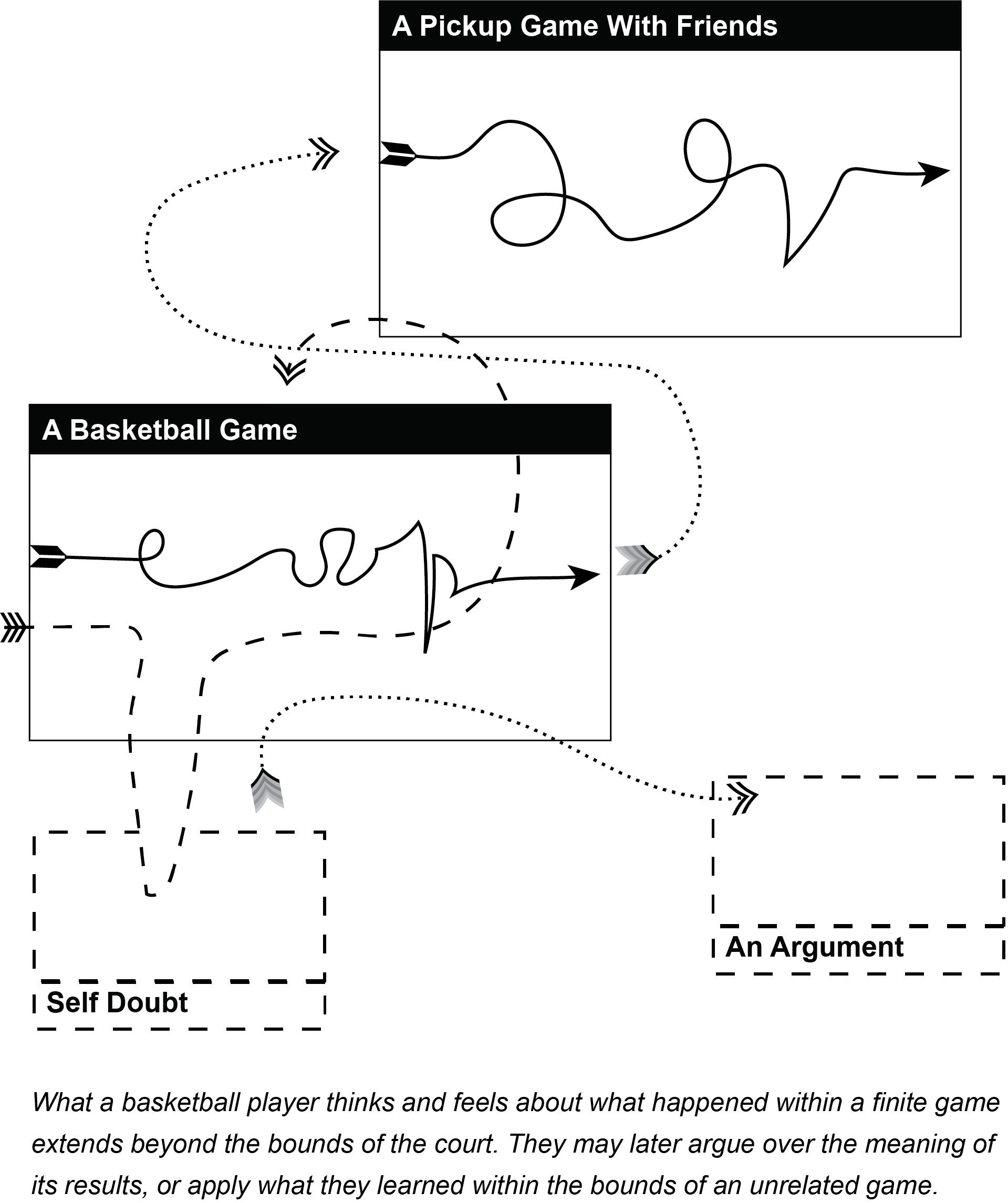

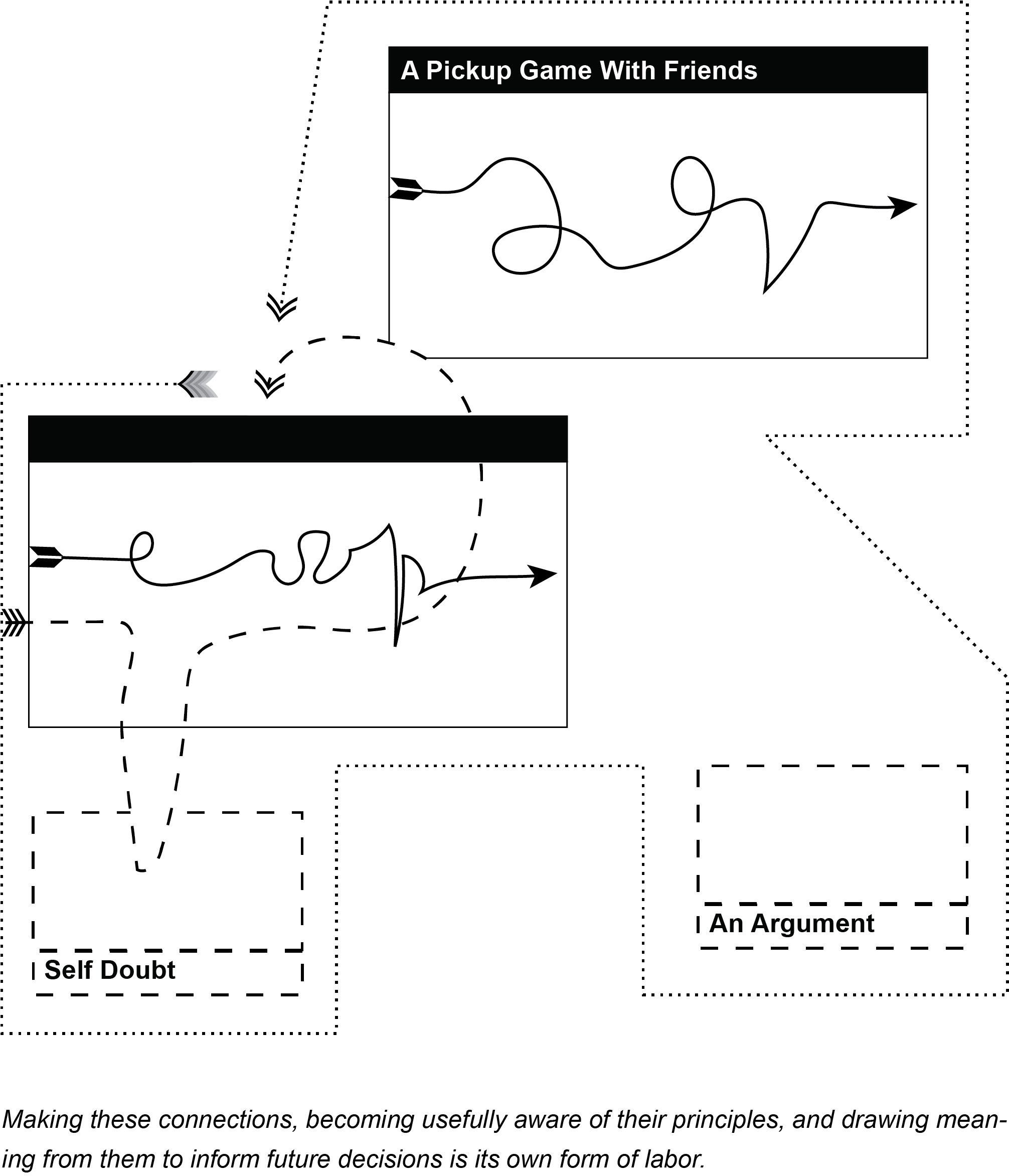

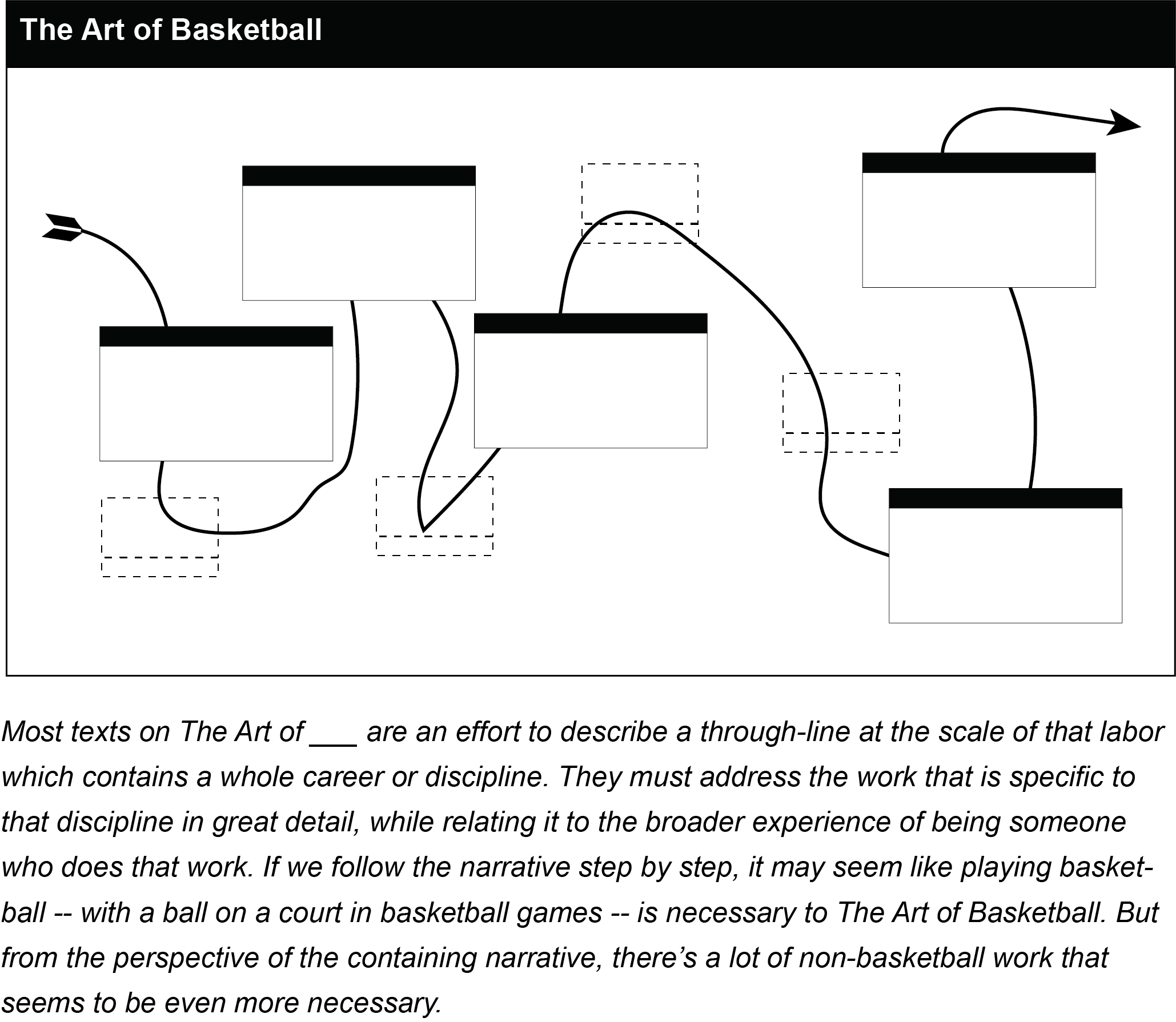

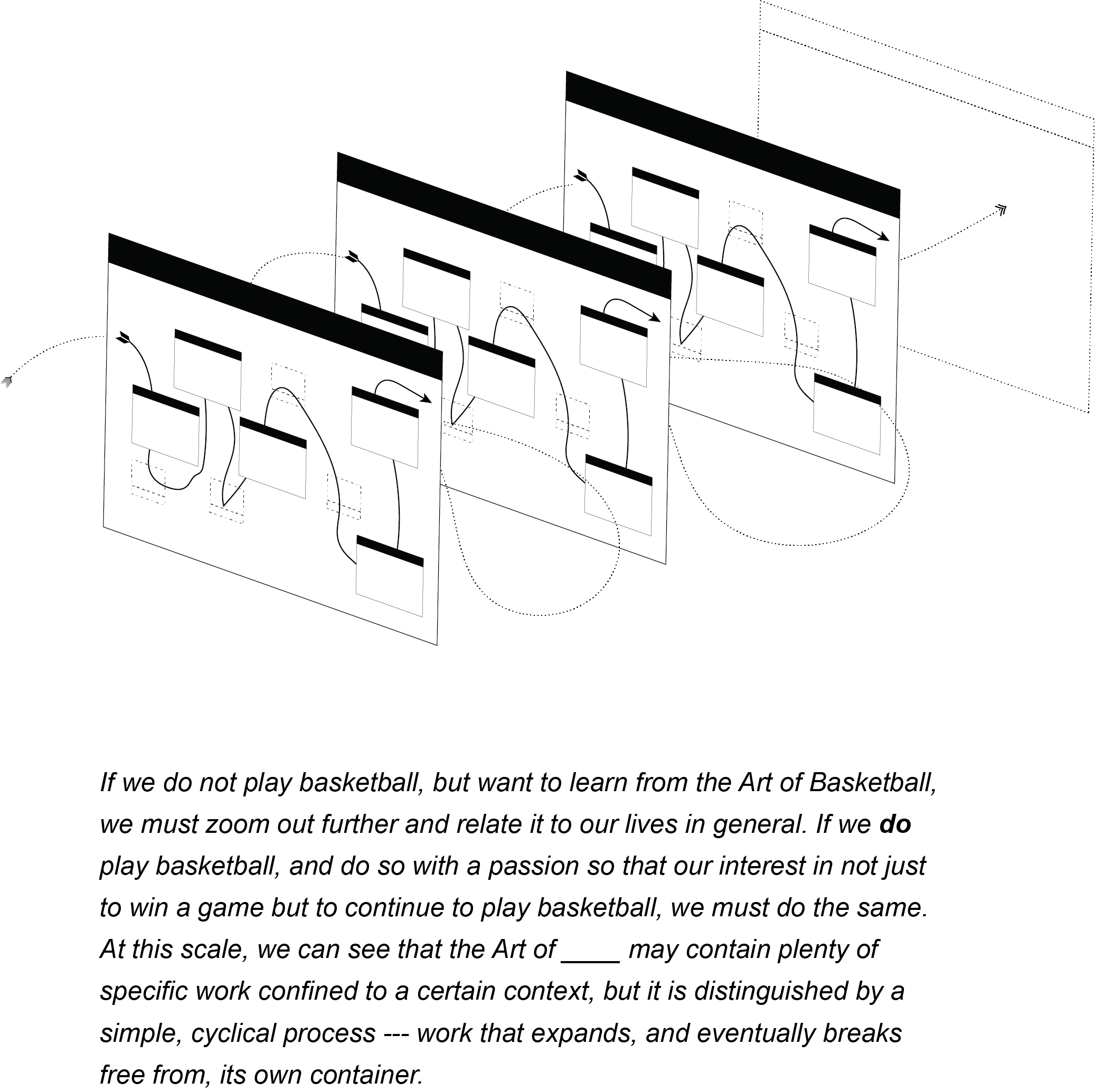

The Art of ___, Diagrammed

Conceptual Labor Counters Power

There is a polemical quality to The Art of ___. It says, while this work may look like the exclusive province of this discipline and those who have the specialized training to do it, the soul of this work can be understood in the abstract and carried to other parts of life. The thing we call, say, windsurfing, is not the Art of Windsurfing. That is a practice of decision making and living that must be continuously refreshed as you walk through life, and there is a way encounter that practice using a windsurf board.

Enough specialists in enough disciplines have made an argument like this that it should be clear that this pattern of working has no originating discipline. If it is transferrable to the “rest of life,” then it actually belongs there as much as it belongs in the lab or the field.

A general theory of conceptual labor, whether it is this Theory or another, must not be confined by external measures or terms. It must apply equally to conceptual labor done at any scale, by any person, for any reason. This proceeds from defining work by the pattern of labor we follow to do it rather than by the contents of the action.

When our actions, experience, and environment can change and change each other simultaneously, we must continuously negotiate the value and meaning of all these things. During conceptual labor, by definition, who we are, why we do what we do, and what qualities of the world at large matter to us while we do it are all subject to critique, redefinition, and re-negotiation. When our conceptual labor contradicts existing notions of how to define a person, what actions to value, or simply how the world is or should be, we have two choices. We can stop doing conceptual labor, or we can insist on continuing the negotiation. This is not the same as insisting that the world is one way when someone says it is the other. It is the act of insisting that the world, and our interpretation of it, be free to change and continue changing.

Conceptual labor knows no discipline

If a toddler and a professional physicist were to take a first-year physics exam, we could reasonably say that the physicist was doing more physics than the child32. That is, they would do more of the work that we call physics to answer the questions. But, assuming they remembered their fundamentals, they will do far less conceptual labor than the child. To simply read a question, the child might have to update their imagined system of the world and learn multiple new words. The physicist mainly has to agree or disagree with the truth of statements according to their deeply held model of the world.

Surely the work of the child is not just of a different material outcome, but of a different fundamental quality. A general theory needs to describe these fundamental qualities regardless of where it lands on Professor Might’s diagram, from where a child labors to understand something at the center all the way out to the very edge, where the physicist labors late into the night in their lab. That is why the diagram is a circle rather than a line — conceptual labor moves from the center to the edge, in all directions, pressing on all boundaries. To pass a physics test is a finite game, but to expand the circle and “keep pushing” is an infinite one.

So, while no respectable science journal would publish the child’s findings, how should we evaluate their conceptual labor? It’s not as simple as grading for effort. As many art teachers have found, students can work exceptionally hard without ever changing their minds. How far did the child expand their sphere of knowledge? How much new mental infrastructure did they construct? Neither of these measures will give us some sort of tidy Conceptual Labor Quotient. Asking them, however, shows that the weight of conceptual labor is a relative value. An adult who had studied opera rather than physics might also struggle with the test, but in their own way. The validity and weight of conceptual labor is determined by the laborer. The terms of the theory make no distinction based on external value.

This is the radical proposition embedded within the very idea that we could hold a general theory of conceptual labor. For its principles to be internally consistent, we must value work by qualities of its doing rather than external measures. Furthermore, we must make room for the critical freedom that conceptual labor requires at any scale. We cannot say that conceptual labor has fundamental qualities at all if we then say, except when we’re talking about this profession or except when these people do it.

Conceptual labor within bounds is not conceptual labor

If we review the many guides to the “art of” something with this proposition in mind, we might understand their polemic tone more deeply. The authors are not just advocating for their preferred techniques, they are trying to promote and preserve a way of encountering the world that sustains free flowing conceptual labor. This, often, is at odds with commerce, which, generally, is the practice of interrupting the flow of something to use its movement for profit. A free-flowing river may support an ecosystem, but we dam it up if we want to support an economy. And, like damming up a river, there are upstream effects to conceptual labor when it is done within predetermined boundaries. The labor we do in such circumstances is no longer an infinite game. Rather it is, as artist and author Jenny O’Dell says, “free within bounds.”33

Conceptual labor that ends at a predetermined point is not fully conceptual labor. That is not to say that all conceptual labor should go on forever, but rather that it must be done with the intention to continue, rather than to reach a known end. We may begin work with a well-defined goal in mind, and we may in fact use conceptual labor to end up there. But the nature of our work changes when the path to that goal becomes unclear. If we must figure out what work is and how to do it while working — that is, if we must do conceptual labor — our goal is unknown, because what we hope to find is no longer an endpoint but a path to that endpoint. We must walk the path to know it. This is the distinction that all the Art of ___ treatises of labor to make — this work is a way, a process, a struggle. It may be done with goals in mind, but it is done with a focus on the labor rather than the product, so that it can freely accommodate unexpected methods and make new goals based on new information.

In this labor, we will inevitably challenge limitations, whether they are our own or those that others put upon us. In this way, the practice of conceptual labor is structurally opposed to entrenched positions and the consolidation of power to maintain them. Whether we redefine social constructs on our way to some other goal, or our if goal is expressly to shift them, we employ conceptual labor to do so. It is inseparable from agency and change.

Controlling conceptual labor for profit: The Executive Map

There is a thriving, parallel market for the literature of “art-within-bounds,” pushed by those who have a stake in containing and exploiting the conceptual labor of their audience. The owners of dams know there’s no point in choking off the river entirely. To sell The Art of ___, one must often allow it to flourish only within convenient limitations.

Art of ___ texts explain that going off map is a different kind of work, and it takes attention and discipline to remain aware of its nature. There is another kind of text34 that is content to say that all you need is a new map — the right map, which happens to be the one the author is selling. These too might appeal to the “art of” something, but only to court association with sophistication, ineffability, high value, unconventional wisdom, and personal expression. Their main purpose is to contain conceptual labor within acceptable boundaries without snuffing it out entirely.

This is an Executive Map, sold mainly on the promise of being a new, better, or unique map. It is the “one weird trick” of critical thinking — by taking one or two steps away from a highly conventional or stereotypical position, it satisfies readers’ contrarian urge without sacrificing a feeling of certainty. Because this map is special, all other maps are trash. By definition, the good routes and advice are the ones that this map contains, so if similar paths show up on other maps, they are simply forgeries or imitations. All this valuable information becomes a systemic appeal to the author’s authority. A rarefied, “artful” approach elevates the virtuoso author’s status — and yours by extension if you follow in their “five easy steps.”

Tony Schwartz’s account of writing Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal is somewhat of a masterclass of Executive Maps. He sees Trump’s systemic belief that “I alone can do it,”35 as the unifying narrative to the “art” the book claims to offer. If this were true, then anyone in need of a map would have no choice but to follow such a leader. The purpose of an Executive Map is not to give readers the tools to figure out their own paths, but to convince them that their leader knows exactly where they are going, and to not ask questions along the way.

This kind of writing, designed primarily to reflect on the speaker, is what Harry Frankfort defines as bullshit in On Bullshit.

Since bullshit need not be false, it differs from lies in its misrepresentational intent. The bullshitter may not deceive us, or even intend to do so, either about the facts or about what he takes the facts to be. What he does necessarily attempt to deceive us about is his enterprise. His only indispensably distinctive characteristic is that in a certain way he misrepresents what he is up to.36

The Art of Bullshit and Politics

The Executive Map is a template for a kind of one-dimensional criticality that can be used to reinforce existing power structures and thwart dissent and authentic critical thought. This Art of Bullshit is a special kind of art-within-bounds, one that conceals its agenda, and must likewise conceal its constraints and rules. While authors and authoritarians waving Executive Maps may primarily be interested in supporting their place in power structures, the bullshit-artistry they describe can function as an independent symptom of entrenched power. It is more of a state than a method — of criticality that stays within the frame that it seeks to change. The Art of Bullshit is what we get if we stop doing conceptual labor artificially, when we feel like it.

Bullshit methodology forwards its agenda in a sideways way by leading the conceptual labor that would dismantle it to instead create a narrative that serves it, thereby containing it. Falsehoods can be disproven, but if they are being done within a bullshit narrative, the fact-checkers are like Mulla Nasreddin searching where there is better light.

Noam Chomsky put it this way:

The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum—even encourage the more critical and dissident views. That gives people the sense that there’s free thinking going on, while all the time the presuppositions of the system are being reinforced by the limits put on the range of the debate.37

Jo Freeman’s influential essay The Tyranny of Structurelessness38 provides an excellent case study of how social groups can default to this dynamic, without a conspiracy to set it up. She outlines how a critical response to traditional organizational hierarchy garnered a rejection of formal structure in the self-organized groups that led the feminist movement in the 1970s. She critiques the positivist narrative of a “structureless” group by showing how, without explicit rules of participation, a “structureless” organization will be shaped by the pre-existing social relationships that members of the group bring with them. The absence of structure is a myth, she says, and it is one that preserves the structures that keep some members powerful and others powerless. Rather than arguing how things should be done within “structurelessness” she reframes the problem with new terminology.

‘Structurelessness’ is organizationally impossible. We cannot decide whether to have a structured or structureless group; only whether or not to have a formally structured one. Therefore, the word will not be used any longer except to refer to the idea which it represents. Unstructured will refer to those groups which have not been deliberately structured in a particular manner. Structured will refer to those which have. A structured group always has a formal structure, and may also have an informal one. An unstructured group always has an informal, or covert, structure.

In her conclusion, Freeman refuses to offer an Executive Map to a quick solution. Presenting multiple narratives to draw from, she advocates for an ongoing critical response to organizational structure in line with the nature and values of the movement’s work.

Contrast this with the way that the Israeli military used post-structuralist philosophy to critically adapt their methods on the battlefield39. They developed a mobility strategy that broke through the walls of private homes rather than using public streets in part because their generals were reading A Thousand Plateaus40, one of the most important books on post-structuralist philosophy.

It’s hard to argue that this was not a thoroughly post-structuralist way of conceiving of literal structures. The Israeli generals didn’t fail to sufficiently understand Deleuze and Guattari, rather they failed to go far enough in applying the theory. They’re capable of dissolving the conceptual boundaries that kept them in an agreement that walls could stop them from going where they desire. However, they’re not capable of dissolving the conceptual boundaries of the framework that locks them into the agreement to desire what they desire. The generals may understand post-structuralist philosophy, but the military cannot.

Why should this be? If the ideas that they employed were powerful enough to dissolve brick and mortar barriers, why should the barriers of nationhood, career, and ethnic identity be immune to such a powerful solvent? It’s because conceptual labor is hard, it happens in the shadows of our intentions and desires, and we avoid doing it whenever we can. Remaining free-within-bounds, we would rather destroy the homes of our enemies than renovate the ideas that hold up our day-to-day model of the world.

However new or special a map is, if it claims to be complete it is of limited use to explorers trying to make their own maps or navigate un-mappable territory. It is through dedicated, ongoing conceptual labor that we understand that we do not just need a new map to our destination, we need to prepare for an entirely different kind of journey.

For Mulla Nasreddin and anyone else looking for something in the dark, this means not going towards the known source of light, but finding one you can carry with you, or maybe climbing the lamppost and cutting it down.

In her essay Poetry is Not A Luxury, Audre Lorde says:

The quality of the light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized.41

The poetry that is indispensable to Lorde is not “sterile wordplay,42” but a process — “the revelatory distillation of experience.” To Lorde, poetry-within-bounds is not poetry. “In the forefront of our move towards change, there is only poetry to hint at possibility made real.” What would happen if we practiced this, the conceptual labor of poetry, and allowed its patterns to permeate our lives at different scales, with different outcomes? Perhaps we could write a book about the poetry of — or even the art of — what we know.

To learn The Art of ___, it seems that we always must cross a gap, the one that divides a concrete practice of writing poems from the abstract pattern of revelation that such a practice has the potential to teach us. bell hooks’s Theory as Liberatory Practice gives us a bridge of sorts, between the abstract practice of theory and concretely personal and political concerns.43

Living in childhood without a sense of home, I found a place of sanctuary in “theorizing,” in making sense out of what was happening. I found a place where I could imagine possible futures, a place where life could be lived differently. This “lived” experience of critical thinking, of reflection and analysis, became a place where I worked at explaining the hurt and making it go away. Fundamentally, I learned from this experience that theory could be a healing practice.

hooks’s appeal to the deep-running social applications of theory is in the spirit of the appeals to a wider audience that we find in Art of __ pieces. But, rather than asking us to expand our understanding of a specific practice to see its broader application, she argues for the power of abstraction that our specific, lived experience already contains. She argues not that one could use theory as a liberatory practice, but that it is, in itself, an expression of that practice. The site of her revelatory theory is not the accepted language of theory used by academics, but the pattern of its practice. Its power can be wielded in the preferred language of the speaker, applied to concerns of personal significance, and understood in social terms that are often denied the status of “serious” intellectual work.

An internally-consistent, general theory of conceptual labor would make such an argument. That if we identify and value conceptual labor as an abstract process, we can see and value it in every part of our lives where we need it, and not exclude it based on appearances or credentials.

When we talk about about legitimizing work that doesn’t feel like “real work,” we’re really talking about the skill to understand that something you didn’t think was important is in fact important, of seeing something that matters that you could not see before.

By saying that, abstractly, this process has a pattern however, wherever it is done and by whoever, we begin outside of the frameworks that tell us what is and what isn’t legitimate work, what is and what isn’t visible. If someone is doing conceptual labor, they are doing conceptual labor. Participating in a society takes labor, and we, historically, have not been very good at understanding and valuing the labors of others. The liberation of hooks’s theory depends on the apprehension of one’s own power to critique the structures that shape our lives, not the ascension to a position where you can play by their rules.

Internalizing a general theory may prepare us to look for — or even expect — the work that has to be done to change the structures that contain our work. If we think of our own, specific conceptual labor in terms of a pattern of work that follows certain principles, we can see that the pattern has no “natural” boundaries. It is a form of working criticality, and it will go on until it resolves or we stop it and say, consciously or not, “this is a barrier I would prefer to leave up.” The poststructuralism of the Israeli generals operates firmly within the bounds of a state military, not because it has nothing to say about the structure of the military itself but because they prefer it that way. They have careers, and status, and a national and ethnic identity that all benefit from the continued existence and actions of the Israeli military.

Poststructuralism is an external label for their conceptual labor, which lends them the lofty ring of a universal set of principles that could apply to the world at large, Israeli or Palestinian. To call their military operations poststructuralist would be, by the technical definition, bullshit. If we instead described what they do in the neutral terms of the Theory, we would have to include a clear description of the barriers and structures they prefer, and the actions they take to enforce them. It is the same in looking at our own ideas, the principles that we think drive our lives. If we step outside their terms and associations, and figure out what we are really working at rather than what we say we are working at, we are bound to encounter some uncomfortable truths.

Conceptual labor means asking “regardless of what I think I’m doing, what am I actually doing?” and then continuously refining your model of your labor — which includes the way you see the world — until it describes what you are actually doing. It only stops when it arrives at an internally-consistent model that has the power to describe new actions taken while subscribing to it. It does not let us stop at politically or personally expedient barriers like the Israeli generals do.

To decide for yourself where you will stop doing conceptual labor to participate in social models44 is an expression of power. The mental cost of participating in many vital social narratives is wildly unequal in its distribution45. Conceptual labor is what we have to do when the conventional narrative fails. A society or institution that refuses to negotiate narratives that demand conceptual labor only from certain members is lying to itself, for the benefit of those who don’t have to negotiate these narratives to survive.

Conceptual labor is the process by which we fundamentally change our model of the world. The more fluent we are in how we practice conceptual labor in the areas that we have the power to control, whether it is poetry or politics, the more we will be able to critique the paradigms that control us.

In this way, The Theory can be used to critique change that occurs within a fixed paradigm, like the radicalism of the Israeli generals46. A critical response to oppressive models that remains within their boundaries is like insisting that poetry is only rhyming verse, that theory is only academic. Its focus on appearance veers towards the technical definition of bullshit.

Radical social change is often presented as a conventional narrative — once the revolution succeeds, we will be free47. This is the tempting notion that paradigm shifts behave like chemical reactions, inevitable with sufficient conditions and fuel. However, it is only through ongoing, cooperative conceptual labor that we negotiate new futures and societies. It is not enough to deliver a vision of the future, it must also be installed and sustained.

If we take seriously the demands and idiosyncrasies of conceptual labor, we can more effectively relate our work to the narratives that frame it. Beyond that, we can practice the special patterns of work that are required to shift our frames of reference. We can prepare ourselves for the narrative to change once we escape it, for it to change once again, and for it to keep changing.

-

Farzad, Houman. “Looking for the Missing Ring.” In Classic Tales of Mulla Nasreddin, Retold by Houman Farzad, translated by Diane L. Wilcox, v. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 1989. ↩︎

-

Might, Matt. “The Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D.” Accessed May 23, 2021. https://matt.might.net/articles/phd-school-in-pictures/. ↩︎

-

Whistler, James McNeill. “The Action.” In The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, 3–5. New York: John W. Lowell Company, 1890. ↩︎

-

Ariely, Dan. “Locksmiths.” Dan Ariely (blog), December 15, 2010. https://danariely.com/2010/12/15/locksmiths/. ↩︎

-

In the field of architecture, the convention of “working on spec” runs counter to this concept. Defined as “any kind of creative work, either partial or completed, submitted by designers to prospective clients before designers secure both their work and equitable fees,” it is antagonistic enough to the actual labor of architects that many banded together to form a group dedicated to ending the practice. Called No!Spec, they fight for the recognition of the conceptual labor that goes into spec work. See https://www.nospec.com ↩︎

-

Daniel Kahnamen’s research into how we frame our decisions based on available knowledge provides thorough support for this assertion. After establishing the influence of framing on problem solving strategies through years of studies, he and his contemporaries now refer to the phenomenon with the acronym WYSIATI — what you see is all there is. Likewise, George Lakoff’s research addresses the effects of linguistic framing on the meaning of statements. See Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. and Lakoff, G., and M. Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press, 2008. ↩︎

-

Cerf, Bennett. Shake Well Before Using: A New Collection of Impressions and Anecdotes, Mostly Humorous., 118. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1948. ↩︎

-

The Labor Theory of Value is primarily associated with Marxism, though it was previously addressed by a number of economists and philosophers before Marx wrote about it in Das Capital. For a contemporary analysis of its adherents, criticisms, and legacy see Keen, Steve. “Use-Value, Exchange Value, and the Demise of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value.” Journal of the History of Economic Thought 15, no. 1 (1993): 107–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1053837200005290. ↩︎

-

See “Knowledge Worker.” In Wikipedia, May 2, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Knowledge_worker&oldid=1021066569 and Pyöriä, Pasi. “The Concept of Knowledge Work Revisited.” Journal of Knowledge Management 9, no. 3 (January 1, 2005): 116–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270510602818. ↩︎

-

Thomas, Lewis. Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher. Demco Media, 1978. ↩︎

-

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Updated with a new preface. Berkeley Los Angeles London: University of California Press, 2012. ↩︎

-

Beck, Julie. “The Concept Creep of ‘Emotional Labor.’” The Atlantic, November 26, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/11/arlie-hochschild-housework-isnt-emotional-labor/576637/. ↩︎

-

Maier, Jean Marie. “It’s Not All Emotional Labor - Clippings.” Clippings (blog). Accessed May 8, 2021. https://thesocietypages.org/clippings/2018/12/13/its-not-all-emotional-labor/. ↩︎

-

Or “How To” or, interestingly, “Against” or “The case for .” Even th simple construction “The ___ of ____” frequently yields good results. ↩︎

-

Knuth, Donald E. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 4, Fascicle 5: Mathematical Preliminaries Redux; Introduction to Backtracking; Dancing Links. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2019. ↩︎

-

Tharp, Twyla, and Mark Reiter. The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life: A Practical Guide. 1st Simon & Schuster pbk. ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ↩︎

-

Elkins, James. Why Art Cannot Be Taught: A Handbook for Art Students. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001. ↩︎

-

Elkins. Why Art Cannot Be Taught, 105 ↩︎

-

Gooley, Tristan. The Lost Art of Reading Nature’s Signs: Use Outdoor Clues to Find Your Way, Predict the Weather, Locate Water, Track Animals–and Other Forgotten Skills. New York: Experiment, 2015. ↩︎

-

Hamming, Richard Wesley. The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach, 1997. ↩︎

-

Argyris, Chris. Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review Classics Series. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business Press, 2008. ↩︎

-

Ayers, William. To Teach: The Journey of a Teacher. Presumed First Edition. New York: Teachers College Pr, 1993. ↩︎

-

Smith, Zadie. “Fail Better.” The Guardian. January 13, 2007. ↩︎

-

Cheng, Eugenia. The Art of Logic: How to Make Sense in a World That Doesn’t, 2018. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=1DA6EB17-A427-4F2D-861C-6172948D52B2. ↩︎

-

Victor, Bret. “Bret Victor, Beast of Burden.” Accessed May 8, 2021. http://worrydream.com/#!/InventingOnPrinciple. ↩︎

-

Linsky, Bernard, and Andrew David Irvine. “Principia Mathematica.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2021. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2021. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/principia-mathematica/. ↩︎

-

Mathematician Kurt Gödel’s 1931 paper, “On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems,” used the formal logic of the Principia Mathematica, thought to be watertight in its ability to express provable statements, to prove that it was incomplete in two ways. “Gödel’s two incompleteness theorems … concern the limits of provability in formal axiomatic theories. The first incompleteness theorem states that in any consistent formal system F within which a certain amount of arithmetic can be carried out, there are statements of the language of F which can neither be proved nor disproved in F. According to the second incompleteness theorem, such a formal system cannot prove that the system itself is consistent (assuming it is indeed consistent).” From Raatikainen, Panu. “Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2021. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2021. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/goedel-incompleteness/. See also Wolchover, Natalie. “How Gödel’s Proof Works.” Quanta Magazine, July 14, 2020. https://www.quantamagazine.org/how-godels-incompleteness-theorems-work-20200714/ and the classic, highly readable Hofstadter, Douglas R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. 20th anniversary ed. New York: Basic Books, 1999. ↩︎

-

Weitz, Morris. “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 15, no. 1 (September 1, 1956): 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540_6245.jaac15.1.0027. ↩︎

-

Warburton, Nigel. The Art Question. London; New York: Routledge, 2003. ↩︎

-

Carse, James P. Finite and Infinite Games. New York: The Free Press, 2013. ↩︎

-

Solnit, Rebecca. A Field Guide to Getting Lost. New York: Penguin Books, 2014. ↩︎

-

The case study in Tenet 7 provides a real-world example where one can watch this happening. ↩︎

-

Odell, Jenny. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, 76. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2019. ↩︎

-

What Maciej Cegłowski. Calls “…wooly business books one comes across at airports (“Management secrets of Gengis Khan”, the “Lexus and the Olive Tree”) that milk a bad analogy for two hundred pages to arrive at the conclusion that people just like the author are pretty great.” from Cegłowski, Maciej. “Dabblers And Blowhards (Idle Words).” Idle Words. Accessed May 8, 2021. https://idlewords.com/2005/04/dabblers_and_blowhards.htm. ↩︎

-

Schwartz, Tony. “I Wrote The Art of the Deal with Trump. He’s Still a Scared Child | Tony Schwartz | The Guardian.” Accessed May 8, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/global/commentisfree/2018/jan/18/fear-donald-trump-us-president-art-of-the-deal. ↩︎

-

Frankfurt, Harry G. On Bullshit, 54. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400826537. ↩︎

-

Chomsky, Noam, David Barsamian, and Arthur Naiman. The Common Good. 5. print. The Real Story Series. Tucson, Ariz: Odonian Press, 2003. ↩︎

-

Freeman, Jo. “The Tyranny of Stuctureless.” Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.jofreeman.com/joreen/tyranny.htm. ↩︎

-

Weizman, Eyal. “The Art of War: Deleuze, Guattari, Debord and the Israeli Defence Force.” Text. Mute. Mute Publishing Limited, March 8, 2006. https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/art-war-deleuze-guattari-debord-and-israeli-defence-force. ↩︎

-

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. ↩︎

-

Lorde, Audre. 2007. Sister outsider: essays and speeches, 36. Berkeley, Calif: Crossing Press. ↩︎

-

Lerner, Ben. The Hatred of Poetry. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016. ↩︎

-

hooks, bell. “Theory as Liberatory Practice.” Yale Journal of Law & Feminism 4, no. 1 (Accessed May 8, 2021). https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlf/vol4/iss1/2. ↩︎

-

This refers to all socially-constructed models, not just norms. Social norms are powerful social models, but “abnormal” social relations carry their own framing power. ↩︎

-

We see this when linguistic code-switching divides along racial lines; some groups can speak “normally” without a second thought, while others must modulate their usual way of speaking to suit a social context that won’t accommodate them without judgement or cost. They must do conceptual labor to model an accepted, unseen narrative so they may understand and adapt to its terms. An early definition of the term appears in Gumperz, John J. “Conversational Code Switching.” In Discourse Strategies, 59–99. Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics 1. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982. ↩︎

-

See also Žižek, Slavoj. “The Prospects of Radical Politics Today.” Žižek.Uk (blog), January 1, 2008. https://zizek.uk/the-prospects-of-radical-politics-today/. ↩︎

-

Or, more darkly, “once we get rid of all this type of person, our country will be strong.” ↩︎