The Expanded Theory

- Tenets 1 & 2: Modeling Labor

- Tenets 3 & 4: Labor Changes

- Tenets 5 & 6: Competing Narratives

- Tenet 7: Patterns and materials of conceptual labor

Tenets 1 & 2: Modeling Labor

Summary

Tenet 1: Labor can be modeled with fundamental components

Tenet 2: Individuals experience work through a unique mental model

Core Concepts

- We work according to our model of work.

- Who we are is part of how we work

- An individual’s internal model of work is their reality of work

- Complex labor requires a model with many properties and rules for how they interact

- Work can be hard to see

- Work changes as you do it

- Comparing models is important, legitimate work

- Conceiving of work is hard work

- Models must be revealed

- Models must be compared against reality

- Models may be applied without being understood

Tenet 1 is the core proposition of the Theory — that we can imagine a useful and dynamic representation of labor — a model — and that we can place the fundamental parts of that representation into three distinct categories. Tenet 2 acknowledges that individuals are the ones doing the imagining, each operating with models of their own conception.

Given any description of a project, we cannot assume that everyone who does the work it demands will understand it in the terms and structure used by that description. Nor can we assume that the description is exhaustive for all circumstances. Even when labor is thought to be “brainless” and routine, we review the conditions of a project and load them into our own mental model. Though this model may refer to external instructions or materials, our models are what we directly engage with.

“What am I trying to do here?” is a classic statement to initiate a new model. We ask this question of ourselves and our circumstances, and then work according to the best answer we can get.

Introduction

What is the end result of perception? What is the output of linguistic comprehension? How do we anticipate the world, and make sensible decisions about what to do? What underlies thinking and reasoning? One answer to these questions is that we rely on mental models of the world. Perception yields a mental model, linguistic comprehension yields a mental model, and thinking and reasoning are the internal manipulations of mental models1.

— Philip Johnson-Laird

A profound divide separates how we experience work as individuals, and the role that our labor occupies in society. We experience work as actions executed by our minds and bodies, but work is traditionally defined and judged by external qualities. Disciplines, jobs, and careers are defined by their appearance, their names, by the effect of a worker’s actions on the outside world, by conventions and materials, and by arbitrary or politicized terms.

There is no guarantee that an individual’s experience of doing work will match the way they are told it should be done, how the results of their efforts will be perceived, or even their own explanation — to themselves or others — of what they were doing and why.

Every project, every problem, every new thing to learn has to be translated from its external conditions into whatever internal language an individual worker uses to comprehend and accomplish work. The conventional narrative of work subjugates this thought process to the external conditions of work, as if an individual’s mind is a black box whose only requirement is that it contain whatever machinery is necessary to process the appropriate inputs into the desired output. The Theory describes how it is the other way round in conceptual labor — that the outcome of work is a property of the worker’s mind.

Tenet 1 declares that, inside that black box, the individual’s state of mind reflects the external qualities of work through what we call a model, and their experience of creating and interacting with that model is significant to their labor. While we can identify three basic categories in which to sort the components of any model, Tenet 2 declares that the actual composition and “feel” of models will vary from one person to the next. Whatever form it takes, an individual’s model is the interface through which they do work. The decisions made, actions taken, and understanding developed by an individual in the course of their work are organized within the paradigm of their specific, up-to-the-second model.

The Core Concepts in this section articulate the significant implications that follow from defining an individual’s experience of work in a detailed model.

Tenet 1: Work can be modeled with fundamental components

The concept of a “mental model” has a well-defined presence in many disciplines including cognitive science, psychology, human-computer interaction, and system dynamics. A handy summary of the history and current state of mental models can be found in the literature review of a 2016 study that asked middle-school students to draw their mental models of Google2.

The modern conceptualization of ‘‘mental model’’ dates back to Scottish psychologist Kenneth Craik (1943), who defined mental models as ‘‘small-scale models’’ of reality (Johnson- Laird 1989; Westbrook 2006)….Doyle and Ford (1998) analyzed these varying definitions and proposed the following conceptual definition based on how the term was most commonly being used within the field of System Dynamics: ‘‘A mental model of a dynamic system is a relatively enduring and accessible, but limited, internal conceptual representation of an external system whose structure maintains the perceived structure of that system’’ (p. 17). A more broadly applicable definition of mental models is offered by Besnard et al. (2004): ‘‘simplified, cognitively acceptable versions of a too-complex reality’’ (p. 119).

Cited above, Johnson-Laid’s article, The History of Mental Models3, traces the multiple origins of similar theories to the late 1800s. Johnson-Laird’s work largely founded contemporary psychological Model Theory, which has grown into an international network4 of researchers continuing to develop the field. The literature of Model Theory is rich, ranging from scientific papers5 to books for general audiences6, and should be rewarding reading for anyone interested in conceptual labor.

Much of Model Theory overlaps with the parallel concept of mental models in user interface design and the field of human-computer interaction, or HCI.

Donald Norman (1983), who subsequently coined the highly relevant term/philosophy ‘‘user-centered design,’’ adapted the term ‘‘mental model’’ for the field of human–computer interaction…. Norman described mental models as people’s continuously evolving cognitive representations of a system that incorporate their beliefs regarding the way the system works. Norman emphasized that a person’s mental model of a particular system both guides his/her use of the system and is iteratively (re)informed by his/her interactions with the system across time7.

More recently, a pop-psychology interpretation of mental models has gained traction in the self-help and entrepreneurial fields8. There, models are presented much like apps, with defined sets of features which they will provide the user once installed, with fairly predictable input and output. Were these models software, they would be considered very “high-level” programs. (Code that executes closer to the machine language that runs the physical computer is, perhaps counter-intuitively, called “low level.”) While useful to many from a self-educational standpoint, presenting models in this way restricts them to a scale and rigidness that, ultimately, isn’t fully compatible with the lower level at which models must operate in the Theory.

Continuing the metaphor, we could say that models in the Theory sit somewhere between the lower level Model Theory and higher-level models of HCI. Model Theory aims to empirically describe qualities of how the human mind operates and interacts with the world, so the rules for its models are borne of research and data. HCI certainly employs rigorous observation in its work with models, but the end use of such data is much more specific — to “provide predictive and explanatory power for understanding the interaction9” between a person and technology. Similarly, the Theory is organized around practical description and useful prediction rather than discovering and describing true principles of human psychology and neurology; however, it aims to provide a framework that operates at a low-enough level that it can describe the interaction between a person and a task of any kind or size that they have set themselves to.

Both paradigms describe models in many ways that support the assertions of the Theory. That models are personalized and must be represented carefully to be understood. That using and updating models is a cyclical process. That models provide more deductive conclusions than can be easily considered all at once by the author of the model. That we can use our prior experience to formulate novel explanations from incomplete information10.

The Theory’s major departure from either discipline is in constructing models with the three types of fundamental components. This is a practical rather than empirical matter — the Theory doesn’t intend to prove that, from a neurological standpoint, there are only these three components of all mental models. Rather, it intends to present a coherent and useful conceptual framework that proceeds from interpreting of our experience of labor according to these three categories. The purpose of the Theory is to assist in comprehending and using one’s own mental models to solve problems, accomplish projects, and self-educate. So conceptual labor should be compatible with Model Theory, the work of HCI, and most other fields that attend to mental models. It is not meant as a referendum on the conclusions of any field’s research, but as a complementary model-of-models to be used in the furtherance of labor of all kinds.

In How to Use the Theory, we diagrammed the components of a model. Here we will examine the basic criteria by which we can define each component, referring back to the example in that section frequently.

The Fundamental Components of Labor

- Actors

- Work

- Context

Actors are anything performing work or work-equivalent actions. An individual at work is the typical actor within a project. However, as we saw in the example in How to Use the Theory, when our model relies on the work done by other parties, those parties become significant enough to be actors, whenever that work was done. We can be co-actors with automated equipment, materials and their properties, other humans, software, corporate policy, and even a set of instructions such as the rules of a game or the directions on a map.

It’s easy to see how active devices like machines and computers can become actors that we must keep track of — often to such a level of detail that we must create a sub-model of their labor. But there’s no reason that a significant, non-human actor has to be something you have to plug in, or even something that actively does new work as you do. Trying to parse a faulty map may require you to imagine the map “diverging” or “forgetting” or “not realizing” things about the land as you build a model that can translate between the map and your experience. Though the map is an inert object in physical reality, it can seem to inflict decisive change within the reality of your model when animated by your conceptual labor.

Work

Work is any action taken by an actor that contributes to their labor. That contribution is a matter of perception and can be designated either before it begins by the actor’s intentions, or later by its results as observed by another actor, or by the actor’s conscious decision to consider certain actions as legitimate work.

Work vs Labor

An important distinction between work and labor is that work belongs to an actor and a context, while labor can contain many actors who can do many different kinds of work in many different contexts. In our example, our conceptual labor encompassed the different types of work performed in each subsequent model, some of which applied to the original task (“hike the trail”) and some of which applied to the models themselves.

In the terms of the Theory, then, labor is the whole process of actors doing work within contexts to complete a project, following narratives produced by their models to do so.

Context

Context is the total set of all conditions that the actors believe to be relevant to the execution of work as part of a project. An actor’s belief is the defining feature. This definition does not suggest that actors can or should know everything that matters to their labor — though it’s certainly exciting to feel that you do.

The belief of each actor is crucial to the central problem in our example. Erroneous assumptions about the conditions of a project are, by definition, treated as true until disproven. The map in our example was neither wrong nor right. It contained ambiguous, static information that our conscious actor interpreted according to the context of their working model.

There are assumptions or beliefs hidden within the definition of what a “map” is, as well as the definition of this particular kind of map. You would expect this map to leave out more information than it contains — you don’t need detailed topographic data as long as you know where to turn.

An expanded definition of Context 1 The Map from our model would include the following beliefs:

The Map

which:

- leaves out information you do not need

- does not leave out information you do need

- accurately represents open, passable trails

- which:

- lead to where you are going

Put this way, we can see that a map drawn by a friend is more like a transit map11 than a geographic record.

These are reasonable things to believe about the map, but they are still beliefs. The map could neither tell you about itself nor update its own content, so we had no outside verification of the definition of this context beyond our observations. When we began to doubt our beliefs, we had to interrogate this context. When we say a map “says” or “shows” something, we treat it as a proxy for the beliefs of its creator. Hence the necessity of adding Context 3 - Model 2 - Your friend.

Context is potentially the most complex of the fundamental components, since our beliefs about the world and our interactions with it often contain many complex models themselves12. When interrogating a context we are not entirely certain of, we are almost guaranteed to find relevant models within it which we have not yet fully defined to ourselves.

Tenet 2: Individuals experience work through a unique mental model

The fundamental components are simply categories, and very basic ones at that. We can use the terms actor, work, and context to distinguish between fundamentally different areas of our labor, but we use much more concrete terms and finer distinctions to actually accomplish work.

Deconstructing our labor into the terms of the Theory is like diagramming a sentence into the parts of speech. It is a structure that only has meaning when we fill it with our thoughts and ideas.

Were this not true, we wouldn’t see the countless workplace and classroom strategies designed to resolve the differences between how individuals conceive of a problem. Over the course of our labor as individuals, we constantly imagine new models filled with specific, momentary meaning. We can do so with shared or personal languages, non-verbal yet specific strategies, and with a freely mixed combination of emotional and rational responses.

We work according to our model of work13.

When we construct these models to work through, they necessarily imply judgements of what is and isn’t legitimate work. At any given moment while working, we strive to do what we consider to be work and to not do anything that we think will get in its way. If we are not passing judgement with our conscious minds, we may do so with our hands simply by where we choose to place them on our materials and tools.

Who we are is part of how we work

The Theory emphasizes the individual’s experience as a defining quality of work, but we can also see that there is an element of subjectivity to how every fundamental component is defined. A human actor’s understanding of the components with which they build their models is a crucial part of their labor.

An individual activates other actors by attempting to understand their behavior. The unseen walls of a maze may stand still, but to someone building a mental model by which to navigate, the imagined walls constantly shift places as they work their way through. This isn’t to say that we must invent a whole personality for non-human actors, but that we can reasonably expect self-talk that affords agency to relevant parts of the outside world such as “the maze goes this way” or, in the case of our map “this path might not be the one I think it is.”

Statements like these are a way of recognizing that existing conditions can be activated by our labor in unknown and dynamic ways. In the Theory, we call these externalities that we perceive14 the context. By definition, context is entirely dependent on an individual’s understanding of it.

The designers of our maze aren’t doing anything while we walk it, but if we find out that they were drunk when they made it, everything around us will seem to change in that moment of clarity.

It’s no great revelation that what we know and understand can affect our labor, but countless states of mind can affect the composition of our models by the same mechanisms. Why we believe something can be more influential than what we believe. Our preferences can become patterns of working, our professional training can shape our very ability to perceive work, and anyone who’s had a sleepless Monday morning should be intimately familiar with the ways in which biology can transform labor.

An individual’s internal model of work is their most “real” version of work

Statements such as “I’m doing this” or “I should do that next,” and their implied conceptual structures construct the mental reality of labor. External qualities of the work are contextualized within this mental reality. This includes evidence of the effects of one’s labor, belief in the the necessity of it, and systematic theories of how one does that labor.

The simplest demonstration of this Concept is an experience we have all had at some point — that of feeling effective while you work only to later discover that you made no progress. This Concept is just another outcome of the executive functions of the human brain. Our mind weaves a coherent narrative from observations and experiences which are only a small sample of the world around us. These narratives are anything but reliable or complete. In fact, many disciplines are occupied with the study of how our minds fill in the gaps, including neuropsychology, visual studies, and artificial intelligence15.

When we recognize that labor is a narrative constructed by an individual, we can see that the “reality” of that narrative is a function of an individual’s perceptions, beliefs and actions as much as it is a reflection of factual conditions.

Complex labor requires a model with many properties and rules for how they interact

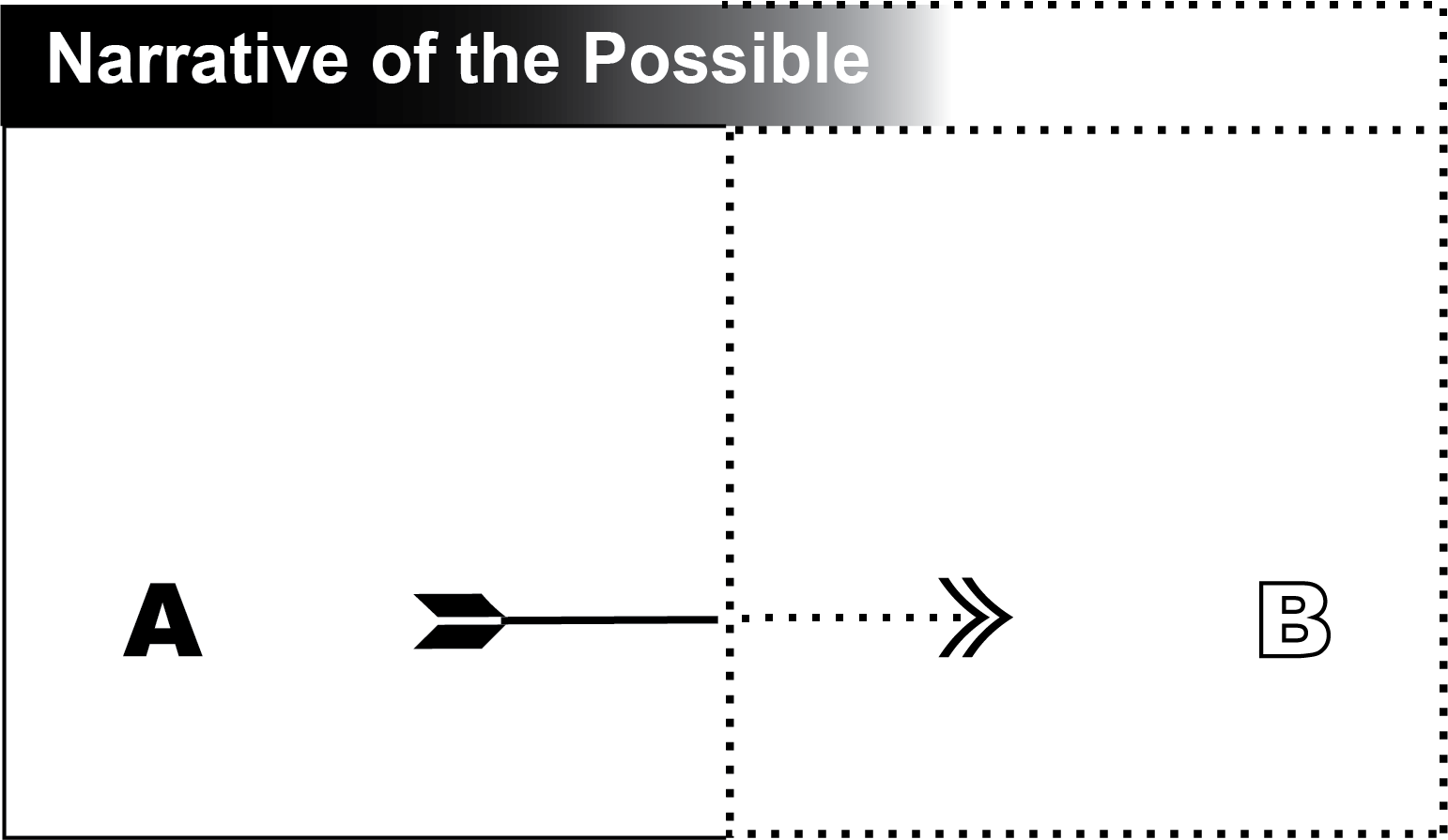

If we understand that such narratives are incomplete by nature, it follows that we would need a method to imagine what a single narrative leaves out. To do so, we must represent the relationships and behaviors of the facts, beliefs, actions, and perceptions that narratives emerge from. A model is such a representation; it is a proposal that things and ideas are a certain way, that they interact according to particular rules, and that they exist in a specific circumstance. Models describe possibilities, while narratives only describe procedure.

Work changes as you do it

Even in the conventional narrative, work changes — it proceeds from incomplete to complete. However, the many possibilities within models present different yet related manifestations of work. The Theory distinguishes between work with static, known requirements and work which changes its own fundamental conditions and requirements as it proceeds.

For example, imagine the work of driving a car. On a straightaway, things (usually) change along one dimension — the car goes from start to finish. But if you are driving cross-country, the nature of what you must do to approach your destination will also change. Driving on a side street requires significantly different work than merging onto the highway or finding parking. A road trip must navigate not just the highways but also the types of driving that must be done, the relationship between all the tasks required to get to the destination, and change its own plan according to the results of their successes or failures. This work has an extra dimension beyond going from Point A to Point B.

Work can be hard to see

Regardless of their complexity or technical difficulty, models can contain work that is neither clear nor obvious. When we choose to work according to one of the many possibilities that a model describes, we do so by momentarily turning away from all the other possibilities. If you were a passenger in a car entering a busy highway, you would want your driver to be focused on the cars in front of them, not thinking of where they’ll eventually park. When we say that we “focus” on work, the metaphor of sight argues that we can pay detailed attention only to a specific interpretation of our labor.

Comparing models is important, legitimate work

Work does not just happen within models — it also happens to them. This is fundamental to the Theory. We do important work by imagining, maintaining, comparing, and understanding models. Given their dynamic and personal nature, we cannot assume, without critical assessment, that any given model will bear out a comparison with alternate models, such as those provided by our observations, obstacles, or our curiosity.

Conceiving of work is hard work

This Concept is explored in depth in the section Expertise Grows out of Conceptual Labor.

Models must be revealed

Models must be compared against reality

Models may be applied without being understood

The complexity of working models and our tendency to focus on the parts that matter most to us means that we can’t assume that we completely understand how they operate before we use them.

Our models are often constructed out of complex concepts that we have absorbed at over our lifetime, especially if we are working in an area which we have studied or trained in extensively. It is easy to assemble a mental model that leads us to surprising conclusions simply because it is hard to consider every possible outcome of a usefully-complex model16. When we think of using a camera in a project, we may think of taking pictures before we think of charging its battery or cleaning its lenses. In the same way that we use computer programs or power tools to do work without knowing exactly how they operate, we don’t necessarily know everything about each concept we use to assemble a model, and often focus only on the features that are of use to us. Creating a mental model of work is a matter of imagination and perception as much as it is a matter of skill or knowledge, and it is subject to all the hazards and critiques that we can apply to perceiving or imagining anything.

Case Study: Good Intentions and Propaganda

Helping vs Being Helpful

Consider the basic idea of help as work. Many of us like to think that we are helpful people. If we are working in good faith, we think that when we are helping, this is equivalent to being helpful. However, a helpful act is defined by its effect on the world, not necessarily the actions of the helper. The basic motion of petting a cat produces very different results whether you do it with or against the direction of its fur.

The things one does to be helpful are defined by their own narrative of what helping looks like. Without doing the conceptual labor required to bring their narrative in line with the present conditions of the work and keep it there, a person who is helping can have the effect of being not helpful.

We can see how helping can sometimes come at the expense of being helpful by plotting our actions on the Helping Matrix:

The Helping Matrix

| Helpful | Not Helpful | |

|---|---|---|

| Helping | ||

| Not Helping |

In the Helping Matrix, one hopes to occupy Helping / Helpful, but can easily land in Helping / Not Helpful if they are not careful. Not Helping / Not Helpful is an obvious position to occupy, but sometimes Not Helping can be Helpful.

Once you have done the conceptual labor to define and identify Helping / Not Helpful a few times, you will see it everywhere.

The Helping Matrix embodies the conceptual labor that it takes to compare the model of your behavior that you believe to the one presented by the evidence of your actions. This is, of course, a fundamental process that applies to nearly any work. One can make matrices similar to the Helping Matrix according to many interpretive pairs, such as:

| Functioning | Not Functioning | |

|---|---|---|

| Functional | ||

| Dysfunctional |

Or

| Is Useful | Is Useless | |

|---|---|---|

| Looks Useful | ||

| Looks Useless |

Or the often devastating Rightness Matrix

| Is Right | Is Wrong | |

|---|---|---|

| Feels Right | ||

| Feels Wrong |

These matrices should not be read as an appeal to objective rationality. They do not imply that there is one way to always end up in the right quadrant. After all, you can be certain of the rationality of your behavior in any of the quadrants. These matrices appeal to the process employed to interrogate your model of reality, and to critically assess the context in which you declare your actions to be rational.

The Uses of Helping / Not Helpful

The Simple Sabotage Field Manual17 can be read as a classic text on the uses of Helping / Not Helpful. Published during World War II by the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor to the CIA), the manual was a resource for citizen resistance in Axis-occupied countries. The tactics within conceal destructive activities behind the allure of the conventional narrative of labor. The plausibility of being a feckless or incompetent worker, earnestly but poorly doing “real work” easily overshadowed the reality of someone doing sophisticated conceptual labor to carefully manage the appearance and ultimate effect of their work.

Since declassified, the CIA has made the Manual available for download, noting that while some of the tactics are outdated, “others remain surprisingly relevant. Together they are a reminder of how easily productivity and order can be undermined.” The agency goes on to list classics, including:

- Managers and Supervisors: To lower morale and production, be pleasant to inefficient workers; give them undeserved promotions. Discriminate against efficient workers; complain unjustly about their work.

- Employees: Work slowly. Think of ways to increase the number of movements needed to do your job: use a light hammer instead of a heavy one; try to make a small wrench do instead of a big one.

We can see this document as a strategic deployment of the conventional narrative as a smokescreen to hide subversive conceptual labor. The sabotage that the OSS encouraged would fit into a highly-plausible narrative in which poor results came from conventional failures — infighting, vanity, or incompetence. This avoided calling into question the instructions and judgments of the occupying Axis troops. The captive workers simply failed to measure up to these correct instructions, a conclusion which did not challenge the Axis model of the world (or the conventional narrative).

This is an important, widespread trick, used by friend and enemy alike, that the Theory can help us critique and resist. The trick is, in short, to tell a tantalizingly simple story about work so that people who might object to its results won’t do the conceptual labor required to see the big picture or question the narrative.

This is the core mechanic of propaganda — weaponizing a simple narrative to prevent conceptual labor. Political and social change and the accumulation of power all require ongoing, coordinated labor. To keep such complex operations on track, the individual models through which the converts work must be normalized and simplified. The active re-interpretation of work that conceptual labor requires is directly opposed to the entrenched agendas that propaganda serves.

Propaganda’s relationship to how we think and talk about about work is apparent in the the sort of contemporary workplace sloganeering typified by Facebook’s infamous “Move Fast and Break Things.” While that individual slogan hasn’t survived the obvious question of “what did Facebook break?” the social media giant is still in the business of spreading reassuring narratives of work. This task was important enough that, until 2019, Facebook maintained a private print studio called the Analog Research Lab to create colorful, high-quality prints that say things like “Stay Focused And Keep Shipping” and “I Am So Thankful for You in My LIKE18.” The ur-message conveyed by the posters that make their way from the ARL to employees’ walls is Your work has known, knowable and good results. You will make the world a better place. Or even more simply put — You are helping and helpful.

From the perspective of the Theory, the mechanism by which propaganda like these corporate slogans hijack our mental models of work is a simple one. Human actors are relieved of the conceptual labor to continuously define and understand the ultimate context in which they work. It can be treated as a fixed quantity, nullifying Tenet 3, and the meaning and effect of all of their actions will proceed from the certainty of this context and inherit its norms and values.

If “connecting people” is the most abstract and basic purpose of all the labor of Facebook employees, and if that is an inherently good thing, then the missteps and questionable practices along the way can be excused because the “mission” is good. Of course there is no room in a busy work week to think “should I even be doing this work?” The challenges facing a Facebook employee can easily be complex and deep enough to exhaust their capacity for conceptual labor. So it’s a practical matter to make sure that workers’ critical powers are focused on the work that serves the agenda of the company and not on the structures and super-structures that contain that work. The friendly, colorful encouragement from an attractively designed poster on the office wall, appealing to deeper human motivations, keeps conceptual labor within appropriate boundaries.

This context-fixing mechanism is the same one that allows “normal” people to support totalitarian regimes. Hanna Arendt famously called this deployment of working norms “the banality of evil.” It is a sort of institutional response to the trolly problem: if it is hard to convince someone to kill another human with their hands, give them a lever. If the target is far enough away, abstracted and collectivized, and enough machinery separates you, your acquired, emotional, and critical models of working will recede. Simple, reliable ones remain such as “I should do my job” or “I should be professional” or, as Arendt saw, “I should do my duty.”

Models can be hard to see

Models must be revealed

Propaganda needs to spread to succeed, so it has to install itself into the minds of individuals who will then repeat and reinforce its worldview. Converts no longer have to look at the posters — they’re repeating the slogans in their own head. These slogans do work in two directions at once. They forward a particular agenda, and they make the actor’s adherence to that agenda more palatable by presenting a simplified context fixed in place by euphemism and a promise of personal advancement.

To meet propaganda with conceptual labor is more than to simply “think different” or “question authority”. When doing conceptual labor, the workings of mental models must be revealed and compared with other models, including the model presented by real-world evidence19. Propaganda models labor — in politics it presents models of the labor performed in social relations and the interpretation of the law, and in our example it models the social effect of the work performed at a corporate job. It’s no use to argue against individual points made by propaganda as long as the debate occurs within the worldview that the propaganda exists to maintain. Propaganda is adapted to resistance, meant to overwhelm, contain, and exhaust argument more than it is meant to prove anything.

Conceptual labor does not commit to a position. Conceptual labor is a continuous process, just as propaganda is, so it is the means by which we construct, critique, and work through models of a world that includes propaganda and self-concealing, bad-faith arguments. Revealing, comparing, and refining our own mental models, continuously as we work, is the most basic process of conceptual labor. If we refuse to do this labor, we can be convinced to believe things we would find repellant if we saw them clearly.

Tenets 3 & 4: Labor Changes

Summary

Tenet 3: Conceptual labor is required when all components of a model are dynamic

Tenet 4: We tend towards models with static and well-defined components

Core Concepts

- Models embody beliefs

- We follow the conventional narrative if we believe that our model has as least one static component

- The conventional narrative is the default narrative of work.

- We have to do conceptual labor because the conventional narrative fails us all the time.

- We resist conceptual labor for many reasons

- It is difficult to redefine work at the rate at which it changes

Though labor involves change by definition, it can still be systematized, described, and planned in effective ways if at least one of its fundamental components can be treated as a known quantity. This is conventional labor — the work we do when we think we know what to do. In this type of work, being confused about the job is not part of the job.

However, work behaves much differently when all significant components are dynamic. When the actor, labor, and context are all able to change on their own accord, and able to change the other types of components, the work takes on another dimension. In this type of work, solving one’s confusion, coming up with new instructions, and executing them are all considered part of the same project.

Introduction

Tenet 3 declares that labor behaves much differently when “all components of a model are dynamic and interdependent” This is the most basic condition of Conceptual Labor — when the actor, work, and context are all able to change on their own accord, and changing one component will meaningfully change the others. In this type of work, managing our environment, solving our confusion, coming up with new instructions, and executing them are all considered legitimate forms of work.

Tenet 4 states that “We tend towards models with static and well-defined components.” In other words, without questioning our beliefs about the conditions of our labor, we will default to the conventional narrative. Critically observing and responding to how and why you work is in itself a departure from conventional labor. There may be compelling reasons to stick with the conventional narrative, but it often turns out not to be true or useful. Conceiving of new, accurate narratives of work while it changes is not easy.

Tenets 3 & 4: Labor Changes and We Must Change With It

Models embody beliefs

Listening for your own laughter is a good way to find evidence of this tenet. Daily life is full of circumstances that reveal the ideas we showed up with to be hilariously, or frustratingly, wrong. You could be looking at art you don’t understand, enjoying an an in-depth conversation with a friend, trying to predict what a client wants, talking to someone when you don’t quite speak the same languages, or trying to figure out why following the instructions that came with a piece of furniture didn’t work.

In each of these situations, think of when and why they might cause you to laugh at something other than a joke. Whether it come from frustration or delight, there is a type of laughter that marks the point when the idea we showed up with breaks to pieces as it collides with reality. Sometimes we watch an absurd but undeniable truth steamroll our perfectly reasonable expectations, and other times we realize that it’s our notions that are ridiculous. Or we simply discover that we had no idea what we were expecting.

This follows from our previous Concept that reminds us that we are often able to conceive of and interact with models that are too complex for us to completely understand all at once. However aware we are of our models, they express assumptions about the state of the outside world, our presence in it, and the conceptual landscape we project upon it. Models are the practical manifestation of the worldview that shapes their assumptions. If we are not completely convinced of this worldview, we must do conceptual labor — we must sculpt our models, examine the beliefs that they embody, and test them against our observations and other potential models.

We follow the conventional narrative if we believe that our model has as least one static component

As soon as we are confident that we can meaningfully define at least one fundamental component of our model and rely on that definition not to change, we can weave a conventional narrative around it. Even if every other component is in chaos, we can at least plot a path from incomplete to complete using our finite component as a reference point.

In the process of doing conceptual labor, we may develop an understanding of our work, our circumstances, and ourselves that will clarify our model enough for us to find conventional narratives within its boundaries20. Our conceptual labor can resolve enough questions and remove enough obstacles that we do figure out where we are going, and can predict what the path ahead will look like.

Though the conventional narrative may seem like the opposite of conceptual labor, we can switch modes at any moment at any scope of a project. When trying something new, such as learning an instrument or playing a new sport, we shrink and expand our context in the process of drilling new skills into our memory. Doing so lets us focus our narrative on the portion of the whole project that we are immediately working on, so that we can crystalize formerly unclear activities into conventional labor that we can reliably accomplish.

This is a powerful and effective pattern of working. We must remember that conventional labor is not an inherently impoverished way of working. Why do the conceptual labor to produce a reliable and robust model if not to take advantage of the clarity it can offer? We often do conceptual labor expressly to produce a straightforward narrative that we can follow with confidence.

While some work continuously rejects conventional narratives, there is nothing inherently wrong with following a conventional narrative that one has arrived at for good reasons. As long as your model holds true, believing that you know what to do is as good as knowing that you do — until something from outside your frame of reference intrudes to prove you wrong.

The conventional narrative is the default theory of work

Whether or not our beliefs are well founded, following them without question will produce a conventional narrative. This is the narrative in which our beliefs are correct, incomplete conditions should be completed, and tools are to be used rather than modified. It is, ultimately, the narrative we follow to do what we think should be done.

The default nature of the conventional narrative gives it a sort of gravity that draws all conceptual labor towards it — it is the most simple and obvious of options. We may quickly alternate between the chaos of conceptual labor and the clearer narratives that we draw from its conclusions, but we tend towards comprehensible work to produce results.

To understand why that is, let us review the the theory of non-conceptual labor — the Conventional Narrative of work.

In the conventional narrative, there are two different kinds of work. The first kind is the work that is directly required to complete a project . The second kind is everything else we must do to be able to do the first kind of work. This secondary work can take the form of figuring out just what it is we have to do, or it can be management and preparation — of our tools, our collaborators, and ourselves. Once we are ready to work, we gather the resources and tools that we know we need, and then we apply them with as much skill as we can, using them to execute our intentions, to do what needs to be done. The difficult parts of this work are being skilled enough, knowing and following the right steps, and working fast or hard or long enough.

If we think this way as workers, then the first kind of work seems like the Real Work. “Real” Work is the work that applies directly to the fundamental needs of a job we wish to do. This is work that would exist whether or not we attempted to do it. A broken pipe must be fixed for plumbing to be done, a novel’s words must be typed for writing to be done, data must be transferred for information to be communicated. The Real Work doesn’t have to be completely known, but it can be completely found out.

The second kind of work is then determined not by the requirements of the job but by the qualities of the worker attempting to complete the job and by the conditions under which they work; how much there is to be found out depends on how much the worker does or doesn’t know. How much information needs to be revealed relies on what obstacles lie in their particular way. None of this, of course, is Real Work — it is investigation or preparation. A perfect worker in perfect conditions would greet a job with total knowledge of what the job requires to be completed, and then do those things without hesitation.21

This is the conventional, linear narrative of work, and it is the default — if not preferred — theory of work in most cases. In this theory, projects are a context in which some conditions have not been met, and work is the process of changing things within that context to meet those conditions. There may be many different paths from start to finish, but this narrative says that these paths are straight by nature, and that they end (with a “thock, ” as Ursula K. LeGuin put it22). If these paths appear circuitous, we blame our efforts to understand them or our working conditions for not being ideal. We feel that we’ve discovered one of these ideal paths when we say “That’s all I had to do?” after expending great effort on something that just wasn’t working.

The idea of Real Work is incompatible with Tenets 1 and 2 of The Theory. The time and effort individuals spend managing mental models would not count as Real Work, nor would the life experience that slowly constructed those models in the first place. Real Work, it seems, is obvious with common sense, so just do it.

Work is not this simple, and we all know it. Yet we cannot escape the conventional narrative. It is like a uniform that fits no one, yet is issued to everyone. Tailoring it to our individual needs seems extravagant or difficult, so we end up piling on alterations and accessories that compensate for a fundamentally dissatisfying outfit.

This theory of work persists not because it meaningfully describes our labor and projects, but because we can use it to measure and plan. Evaluating the success of a job is easiest when the job and the work done to complete it are both definable and finite. The conventional narrative is only a useful illusion, not a fundamental condition of all work. It is the illusion favored by institutions and individuals whose success relies on easily communicated value, smoothly repeatable transactions, and the appearance of competence.

We have to do Conceptual Labor because the conventional narrative fails us.

To repeat a previous section, doing the wrong work is a problem even if you do it well. The very existence of the cliché “work smarter not harder” is evidence of the false dichotomy, supported by the conventional narrative, that gets us into this situation. Why should working “smart” and “hard” ever have been separated? Smart is not inherently easy, hard is not inherently stupid.

Following the conventional narrative too far, even in good faith with “the best and the brightest” on the problem, can still lead to an application of the “right” solutions to the wrong problems, or at the wrong times, or in the wrong amount, or in some other capacity that is wrong for a reason no one understands.

Our tendency to avoid conceptual labor and our preference for models with at least one fixed component as stated by Tenet 4 causes systemic problems when work is as fluid as Tenet 3 describes.

This brings us to our next core Concept of Conceptual Labor

We resist conceptual labor for many reasons

The Core Concepts of Tenets 1 and 2 outlined the way in which doing conceptual labor can be difficult. Besides the fact that it’s generally easier work when you understand what you’re doing, there appears to be a deeply-rooted pattern of human psychology that resists the conceptual labor required to critique the conventional narrative of our behavior.

We can see evidence in the body of research supporting “dual-process23 theory,” which separates the mind into System 1 and System 2 thinking. Daniel Kahneman defined them this way in his popular Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow24:

- System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.

- System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration.

A common thread of Kahneman’s work is how reluctant humans are by nature to engage System 2. Unsurprisingly, his research frequently addresses how we physically see the world. Optical illusions, attention, and what is called associative coherence offer insight into the way that the brain, via System 1, subconsciously constructs a coherent picture of an often chaotic world. The field of visual cognition dives further into the specific behavior of these phenomena. The Thinking Eye, the Seeing Brain, an accessible introduction to the field, opens with a list of common assumptions about perception which have been repeatedly disproven by experiment.

- the myth that seeing provides a faithful record of the world in front of us

- the myth that seeing occurs automatically and without any thoughtful activity on our part

- the myth that our eyes are responsible for our sight

- the myth that we can think without using our senses25

Neuroscience has shown that the underlying, biological mechanics of how the brain tells a useful story of the world are far less reliable and unbiased than we once thought26. It seems that there is something about our brains that prefers to follow straightforward narratives rather than navigate the murky territory where we find conceptual labor.

While there is no end to the ways in which we can be enticed by a conventional narrative, our motivations to overlook conceptual labor often fall into one of the following categories.

Politics

Stakeholders in a certain narrative may characterize it as logically obvious as part of a bad-faith argument in favor of keeping things the way they want them to be, or to provoke a certain reaction.

Strategy

Even when knowing that conceptual labor is important and required for the work that you’re doing, there are real-world limits on how much exploration and questioning one can do. Many disciplines are defined by the structures put in place to manage and segregate conceptual labor from conventional labor27.

Identity

The established, most-visible narrative of a job may be central to an individual’s worldview, and questioning it may be intensely destabilizing.

Perception

Conceptual labor is hard and hard to see, so it is common to overlook even when doing earnest work in good faith. “Functional fixedness” is a common term for this.

Perspective

Individuals doing labor understand it differently than observers watching them. It makes sense that they would disagree as to the nature and character of their work.

It is difficult to redefine work at the rate at which it changes

The subjectivity of the term “difficult” is relevant to this concept. For any way of working, easy tasks will be treated differently than difficult ones. This Concept is simply a warning not to treat this task as easy.

Rate, here, is not a matter of speed as much as it is proportional, dependent change. Our actions set the tempo of our labor. We can imagine fast fluctuations in the context of musicians or surfers, but big, slow moving problems can outpace our ability to change our minds through pure complexity or depth. The implications of changing part of one’s worldview cascade quickly through the rest of it, and it is easy to be caught doing irrelevant or wrong-footed work while trying to update your working models.

If we think of adjusting a model and doing work as separate actions, trying to keep them in sync must be a continuous, cyclical process. While labor remains conceptual, updating your model will redefine your work, and vice versa. They must both keep up with each other.

Case Study: Industrious Fictions

There is a tension between the assertions of Tenets 3 and 4. These two tenets say, essentially, that conceptual labor involves complex, multi-dimensional change, but as humans we prefer to do straightforward work. This tension drives many stories of best laid plans gone wrong, and can be useful in trying to understand what Horst Rittel and Melvin Weber called “wicked problems.”

The problems that scientists and engineers have usually focused upon are mostly “tame” or “benign” ones. As an example, consider a problem of mathematics, such as solving an equation; or the task of an organic chemist in analyzing the structure of some unknown compound; or that of the chessplayer attempting to accomplish checkmate in five moves. For each the mission is clear. It is clear, in turn, whether or not the problems have been solved. Wicked problems, in contrast, have neither of these clarifying traits; and they include nearly all public policy issues–whether the question concerns the location of a freeway, the adjustment of a tax rate, the modification of school curricula, or the confrontation of crime.28

We can see the roots of this opposition in a deeper disconnect expressed by Tenets 1 and 2. While Tenet 1 lays out some terms to describe an individual’s experience of labor, Tenet 2 recognizes the boundless variation of that experience. The core concepts of Tenets 3 and 4 are borne out of the impossibility of understanding the subjects of our conceptual labor without critiquing the models that mediate our contact with them.

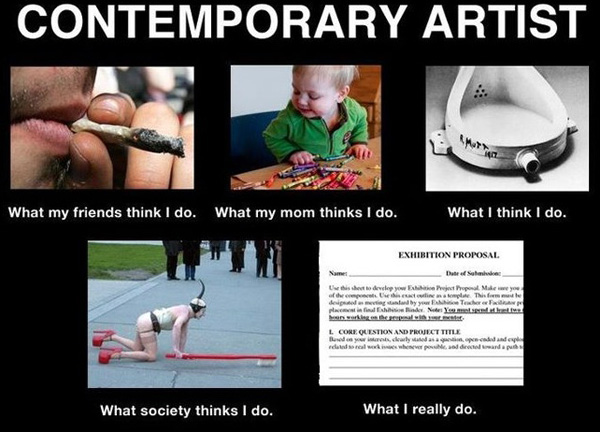

Models embody beliefs

The meme What People Think I Do / What I Really Do29 demonstrates this Concept on a broad scale. Popular enough to merit its own generator30, the format laid bare the beliefs embodied in the way that different perspectives modeled the labor of professionals. The joke lands whether or not you do the work in question; the panel “what I think I do,” is just one of many perspectives implicitly compared against “what I really do.” However you see the professions in question, it touches on the shared experience of trying to model what you “really do”. Whether they come from your family or your own biases, perplexingly-durable clichés surround labor that we all have to resist falling into sometimes — scientists must wear lab coats, all artists storm about with palettes and brushes, and lawyers mainly give speeches in courtrooms.

Meme image by artist Garnet Hertz that popularized the format.

Meme image by artist Garnet Hertz that popularized the format.

When we sit down to work, we do so through a model of our labor in our head, and with it comes a variety of beliefs and assumptions. We work according to that model, subject to the implications of the picture it paints, whether we understand those implications or not. Anyone who has watched a robotic vacuum bash itself repeatedly into a corner has seen a real-world example of this.

The vacuum is an actor that has reached the limit of its ability to do conceptual labor. However much its training, foreknowledge, or programming allows it to learn, the unseen wall represents the boundary of its ability to modify its own instructions. Attempting to do the work that fits its limited model of the world despite the ways in which reality has contradicted it, it performs useless actions that appear pathetic to observers who can do flexible, continuous conceptual labor.

We follow the conventional narrative if we believe that our model has as least one static component

The cornered robot is following its beliefs, but for a more functional example of how this works, consider being lost in a city completely unknown to you.

Example

If you know the name of where you are going but have no map, and no guide, you will definitely have to do conceptual labor get to your destination.

If you do have a map, then your context is static and independent of the other components. The realm in which you have to work was previously only defined in your imagination — a city of unknown and infinite possibilities. Assuming it’s an accurate map, your work to get to your destination won’t change the map. Knowing your context, you can engineer a set of reliable instructions to get to your goal. The map and the journey will certainly change you, the actor, but again the map remains fixed.

Now, if you don’t have a map, but you have a set of directions to follow, you can still escape the difficult conceptual labor of being completely lost. (Directions here define the work of your model.) You may change along the way as you learn things about the city, and your context will change as you build a picture of the corner of the world through which you travel, but as long as you follow your directions — your unchanging work — your labor will proceed from incomplete (lost) to complete (at your destination).

This example gets more philosophical if we must imagine how you, the actor, could resist changing. Either you are so obstinate that you will not admit that you are lost, or something must prevent you from observing and learning from your surroundings. It’s easier to imagine a robot than a human acting this way, but when we refuse to adjust our models in the face of contradictory evidence, we begin to resemble these robots.

A robot bashing into a wall does so within the conventional narrative, not from a consciously-held purpose. When our labor is unexamined, it will always end up following the conventional narrative, at any scale.

The conventional narrative is the default narrative of work.

A robot bumping into a wall doesn’t know it’s wrong. The most common reasons robotic home vacuums bash into furniture or walls are blocked sensors or lighting conditions that hide obstacles from the device. Our robot cannot avoid what it cannot see. It follows all of its rules perfectly within the worldview it is capable of assembling, and cannot critically observe its own behavior and beliefs “from the outside.” Since we can see the limits of a robot’s ability to do conceptual labor, we can see how the work it does beyond those limits defaults to a conventional narrative.

Because there are fixed boundaries to how much the robot can change as an actor, its beliefs are inherently always “correct.” Because its work is also contained within a finite set of possible actions (however sophisticated those actions may be), it attempts the actions required to take incomplete work to a state of completeness even when they are ineffective. The context in which it works is even more confined than the rooms that it cleans — it works entirely within a world of its own measurements and observations, lacking the ability to generally perceive and model its environment through abstract inferences31.

There’s an obvious discrepancy between where walls are in the real world and where they are in the robot actor’s working model. But we would do well to remember that “obvious” is a matter of perspective here. Even when many experienced, intelligent people collaborate in good faith to break big problems down into conventional narratives that can be solved, they can miss salient aspects of reality until it’s too late.

We have to do conceptual labor because the conventional narrative fails us all the time.

The proof of this is all around us. When we watch a robot bash into a wall from an ironic distance, we stand in the same position from which we view our past mistakes — a context that exceeds the boundaries of the context that contained our work. It is when we cannot or do not do the conceptual labor to find such a context that we confidently execute our plans according to faulty models.

Example

Something unexpected happened when the Millennium Bridge first opened to the London public in June of 2000. Thousands of pedestrians flocked to the iconic walking bridge, and while it was certainly strong enough to hold all of them, it demonstrated “synchronous lateral excitation” — it swayed an alarming distance from side to side. No weakness was found in the designs that could account for this behavior. The high-profile bridge “surpassed standards for withstanding weight and wind. Every nonhuman element had been tested.”32

Modeling the human element was the key to an eventual solution. The bridge was designed for a degree of flexibility, but it flexed at a frequency that closely matched that of human walking. That shouldn’t be a problem with hundreds of pedestrians walking at their own rate, out of sync with each other.

We could very reasonably model that situation, in accordance with a sophisticated understanding of physics, in this way:

Model 1

Project: Get hundreds of pedestrians across a river

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | Hundreds of individual pedestrians | Self |

| Actor 2 | The Bridge | None |

| Work 1 | A1: Walk across the bridge | Self |

| Work 2 | A2: Respond to W1 within engineering regulations | None |

| Context 1 | A bridge full of pedestrians within designated limits | None |

Components’ ability to affect each other to a degree that is significant at this very high-level of modeling have been effectively engineered away. A bridge that could be significantly distorted by the crowds walking over it would not be erected in the first place. Whether it would even be considered a bridge is in question.

However, the crowds spontaneously began to sync up with each other — and the bridge.

It turns out33 that people walking on a bridge that starts to shift will instinctively adjust their stride to match the bridge’s swaying motion as it lurches sideways. This will be familiar to anyone who has tried to walk on a fast-moving train and needed to find steady footing as the train wobbled from side to side. But on a bridge, this exacerbates the problem, giving rise to additional small sideways oscillations that amplify the swaying34.

A feedback loop quickly emerged from the sidesteps of the crowd and the slight wobble of the bridge, creating a mass, synchronized rocking motion that caused the bridge to flex much more than expected. In videos of the event, the bridge appears to shake while pedestrians struggle to keep walking in a straight line. In reality, the pedestrians are the ones shaking the bridge, but they all adjust their gaits in time to maintain forward motion, resulting in massive, synchronized lateral forces35.

Model 1.1

Project: Get hundreds of pedestrians across a river

| Label | Component | Can affect |

|---|---|---|

| Actor 1 | Hundreds of individual pedestrians | Self, A2, W1, W2, W3, W4, C1 |

| Actor 2 | The Bridge | A1, W1, W2, W4, C1 |

| Work 1 | A1: Walk across the bridge | Self, A1, A2, W2, W3, W4, C1 |

| Work 2 | A1: Don’t fall down | Self, A1, A2, W1, W3, W4, C1 |

| Work 3 | A2: Respond to W1 within engineering regulations | Self, A1, A2, W1, W2, W4 |

| Work 4 | A1: Respond to W3 | Self, A1, A2, W1, W2, W3 |

| Context 1 | A flexible bridge full of pedestrians within designated limits responding to each other and trying not to fall down | Self, All |

The changes here all seem obvious — of course pedestrians don’t want to fall down, of course they will respond to a movement in a bridge, of course they are all human with human instincts. It’s the way that those obvious yet significant qualities can all affect each other that created the emergent behavior that shook the bridge. The bridge eventually re-opened with an asymmetrical set of dampers to prevent regular patterns of flexion.

For all the successful conceptual labor of the engineers (or the advanced programming of the robot) to break big, vague problems down into smaller ones with solutions that can be engineered or calculated, the failures came not from proposing bad answers to tough questions, but from failing to ask the questions that were not answered at all. The robot does not see the wall, the engineers did not model the human factor, yet they have done all their known work, as it was defined, with great competence and skill.

We Resit Redefining the Narrative for Many Reasons

The engineers of the Millennium Bridge freely admitted what they missed and made the necessary adjustments once they redefined their working models. However, we can’t assume that everyone will, in good faith, do the conceptual labor required to resist conventional narratives and maintain detailed and accurate models of their labor.

Conventional, fixed, or stereotypical narratives can be useful illusions. By focusing their efforts on supporting the established narratives of their work, individuals, organizations, or whole industries end up directing their efforts away from producing their desired effect to representing effectiveness — to look like they are helping, not necessarily to be helpful. This representation is, like our meme, interpreted according to a Conventional Narrative. It can be a narrative designed to convince outside observers, or, like the propaganda in our first case study, directed at yourself to justify your worldview. It can rationalize a situation that benefits you, or simply create a self-reinforcing picture of the world — like the pedestrians’ idea that they were walking forward, not sideways, on a shaky bridge.

We can find troubling examples of this in any profession. Nonprofits and NGOs develop what nonprofit director and theorist Vu Le calls a “shadow mission”

which is often to get as much funding as possible, grow as big as possible, even at the cost of program quality or staff morale, and screw anyone who gets in their way36.

Technologists have “the Shirky Principle” from writer Clay Shirky: Institutions will try to preserve the problem to which they are the solution.37

And from 2008 to 2009, a police whistleblower38 at the NYPD used secret recordings to catch his department systemically manipulating CompStat data to produce politically desirable outcomes — what the TV series The Wire called “juking the stats”.

Bad-faith examples illuminate the deeper problems of sticking to work that looks like work “should” — it will let you down when you’re trying to solve really complex problems.

It is difficult to redefine work at the rate at which it changes

Sociologist Charles Perrow coined the term “normal accidents” to describe the inevitability of accidents within systems that have all three of the following qualities:

- Complex

- Tightly coupled

- Potentially catastrophic39

Human error in such systems is “normal” because it proceeds from rational decisions or predictable responses. The term “tightly coupled” refers to the small or nonexistent margins between components — change in one area will precipitate change in many others at the same time. Tenet 3 describes how conceptual labor functions as a tightly-coupled system. Normal accidents, alas, follow Tenet 4.

For an example of a deadly, normal accident that, despite occurring slowly over decades, outpaced the conceptual labor required to comprehend it, we can turn to the obsolete disease of thymic asthma. Doctor Jeffrey Ritterman told its story in the Permanente Journal in 201740

In the first half of the 19th century, physicians were becoming alarmed by sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Healthy infants would be put to bed and found dead in the morning. In 1830, pathologists noted that SIDS-affected infants had enlarged thymus glands compared with “normal” autopsy specimens. It seemed logical to conclude that these “enlarged” glands were in some way responsible for the deaths.

In 1830, the term “thymic asthma” was introduced to describe the “enlarged” thymus glands that pressed on infants tracheas and suffocated them from inside. Surgical removal of the gland had an “unacceptable” rate of mortality, while radiation treatment seemed safe and effective by comparison. So, thousands of responsible parents, on the advice of trusted medical professionals, had their children’s thymus glands irradiated in an effort to shrink them. It is estimated that more than 10,000 thymic radiation “therapy” patients died from cancers later in life before irradiation of the thymus was declared, in 1945,“an irrational procedure at all ages.”41

Knowing what we do now about radiation, this outcome is sadly obvious. However, the deeper error in this story could not be found out within the bounds of the original problem. The thymus glands were never enlarged.

The cadavers used by anatomists to determine the “normal” thymus size were from the poor, most having died of highly stressful chronic illnesses such as tuberculosis, infectious diarrhea, and malnutrition. What was not appreciated at the time was that chronic stress shrinks the thymus gland. The “normal” thymus glands of the poor were abnormally small42.

The thymuses in otherwise healthy infants that died of SIDS were, in actuality, the first large set of normally-sized thymus glands studied by medical science.

It’s tempting to say that this was the result of a lack of knowledge. Had we known more about radiation, or cancer, this certainly wouldn’t have happened. However, the “problem” to which radiation therapy was only one possible solution didn’t even exist, and no one would have figured that out by learning more about radiation. Even if we learned everything we thought was possible to learn about the thymus, that wouldn’t have helped. We needed to expand the boundaries of what the problem was, what could be known about it, and change the ways we drew such lines.

Doing so collided with the boundaries of medical authority, turning absolute knowledge into relative and biased data. The requisite shift in worldview took decades to propagate through the medical profession. Identifying recent medical “facts” whose disproval met with significant resistance, Ritterman makes this appeal

To avoid future errors and their associated harm, I suggest a cultural shift encouraging professional humility and greater questioning of medical dogma. Medical education focused on teaching students this history may help with this cultural shift.

This is not an appeal for better research methods or to fix a lack of education. Rather it wants for more flexible models, ready to redefine the ever changing work of doctors — for more skillful conceptual labor43.

Tenets 5 & 6: Competing Narratives

Summary

5: Conceptual labor requires actors to continuously update their models

6: Part of conceptual labor is understanding and explaining why it is necessary

Core Concepts

- Doing work and modifying the narrative of how you work must happen simultaneously

- Work that modifies its own narrative is a conversation

- In this conversation, we must represent our experience

- The ideal state of this conversation is spontaneous, continuous agreement

- Successful conceptual labor cannot be fully planned, only cultivated

There is work involved in understanding why conventional labor fails or why a narrative of how one should work is wrong. When the conditions of work meet Tenet 3, conventional labor is no longer effective, but it is the mode we will employ by default (Tenet 4). Therefor, attentiveness and sensitivity to the changing requirements of a project can be considered skills in their own right.

Introduction

Tenets 5 and 6 and their core concepts proceed from the effort to clearly perceive conceptual labor and to distinguish it from conventional labor.

Tenet 5 says that if one’s working model is to stay in sync with their labor as it changes, they must continuously update it. As Tenet 4 has shown, when we settle on a definition of work, our labor tends towards the conventional narrative.

Tenet 6 is an outcome of this necessary conversation about what work is, should, or could be. Conventional labor proceeds according to its authority as being effective and necessary. If conceptual labor begins when we question that narrative, then it must include an argument for the necessity of conceptual labor and the new narratives it produces.

Doing work and modifying the narrative of how you work must happen simultaneously in conceptual labor

Conventional labor can be done when at least one of the three fundamental components of work is expected not to change. So it follows that, in contrast, we must do conceptual labor while all three types of components of our working model, including the work it contains, are in flux. Since that is a definitional quality of conceptual labor, discussing this Concept risks becoming circular. We must recognize that the beliefs and intentions of actors doing work can take an active role in determining whether or not work occurs at the same time the narrative that it follows is being modified. The same activities which require deep conceptual labor from an inexperienced actor may be able to comfortably follow a conventional narrative for experienced actors, in which “real work” is separate from metawork such as preparation and management.

Example

If you’re learning to play the guitar, you will greet a practice session of scales and drills you know with a very different narrative than you would one that introduces new material. The distinction between a “new” and “known” scale is one of degrees until it passes a certain threshold, whether suddenly or gradually. So it is not our definition of conceptual labor that predicts how sure of a passage the musician will be during a practice session, it is how sure the musician is of a passage that distinguishes what kind of labor it requires to play.

A thoughtless repetition of known scales and exercises is conventional labor, but a practice session that even threatens to contain unknown material becomes conceptual labor. The session becomes a flexible context, in which the musician watches for and considers the relationship of unknown passages to known ones — assembling a model of what they know, what is happening, and what they’re doing at the same time that they do it.

Discussing this Concept can be useful as a way of critically examining exactly how simultaneous work actually is with meaningful observation of it. The question of shared duration is important — work may appear to finish before its effects have fully propagated or certain actors believe themselves to be finished. In the end, the model defines the timeframe in which work occurs, and if this timeframe allows for meaningful self-modification to the model, the conventional narrative will fall apart and conceptual labor becomes necessary for the duration of that timeframe.

Work that modifies its own narrative is a conversation

This kind of work can be an argument, a debate, a discursive ramble, or any other kind of conversation, but it cannot be a lecture. If our conversation is just a string of declarative statements to describe work, we already have a name for that — instructions. Instructions imply the conventional narrative not just by being defined but also by being authoritative. The conventional narrative is singular by nature. To negotiate, argue, or modify the conventional narrative is, as Tenet 4 states, to switch to conceptual labor. Conceptual labor is work that accepts the possibility of multiple legitimate narratives at once. As the previous core Concept demonstrates, the uncertainty of conceptual labor may resolve into conventional narratives at countless stages and scales. With conversation as a metaphor, we can see the difference between conceptual and conventional labor as the difference between negotiating potential narratives and agreeing on one. Whether the negotiation resolves quickly or continues for a lifetime, we must recognize that argument and agreement are two different states.

In this conversation, we must represent our experience

Whether we are working alone or socially, the conversation of conceptual labor must integrate our experience of work with the available narratives that describe it. By definition, conceptual labor requires a self-modifying actor. Tenet 2 details the role of conscious actors in conceptual labor — actors with a general sense of their own experience. Carrying on through Tenets 3 and 4, we see that not only do we experience labor through our models, our concurrent experience of using and testing those models is a necessary element that must be also represented in our models if they are to be robust and detailed enough to be of use. Even a momentary representation implies a position — a belief in a set of significant qualities that describe our experience of the work. Representing our beliefs in a model doesn’t require us to fully understand them. We can infer a position from a representation even if it is not fully explained.

In conventional labor, this representation and the position it supports are irrelevant if they don’t fit the conventional narrative — that is unless they have the authority of Real Work. Conceptual labor, however, requires us to recognize that we have an experience, and for it to inform a position we must represent it.

In doing so, we must also recognize that representational strategies, the subjectivity of experience, and the vagaries of perception are crucial to understanding our conceptual labor.

The ideal state of this conversation is spontaneous, continuous agreement

This Concept is a necessary addition to the previous one. While we may represent certain positions and beliefs in the process of conceptual labor, we must recognize the plurality of valid positions and cultivate the flexibility to navigate to new ones. Positions are proposed and taken in conceptual labor, but when they are held fast, a conventional narrative emerges.

We have all encountered conceptual labor that never completely resolves into conventional labor. We variously call this sort of work a career, a relationship, a calling, an art, or something else entirely. This kind of work defies the ideal state of conventional labor, where a perfectly-skilled worker completes the work with minimal effort to perfect results. This work follows the rules of infinite games44, where the ideal state of the players is one of ongoing, simultaneous discussion and agreement. We observe the rules of infinite games, says Carse, “as a way of continuing discourse with each other….the rules…are always evolving to guarantee the meaningfulness of discourse45.” The game will continue, and continue to change, as long as the players agree to the changing rules.

Disagreements can occur within those rules as long as they don’t put an end to play. It is the agreement to continue that matters.

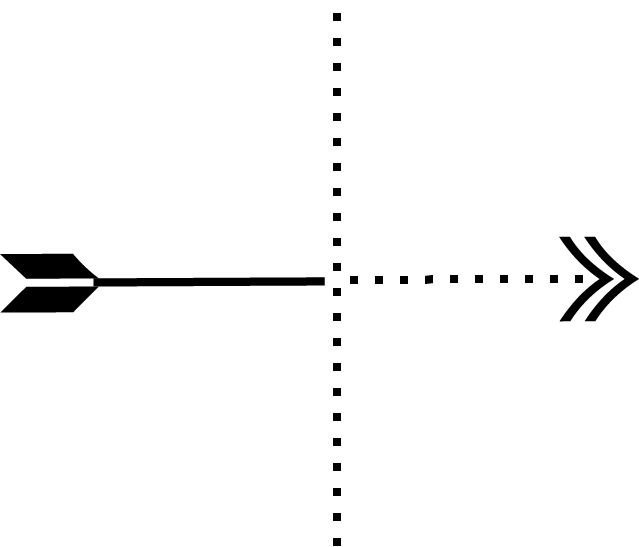

Labor that acts on itself is cyclical

As long as we “agree to keep playing, ” our conceptual labor will progress in cycles. Tenet 3 establishes how the actors, work, and context may all change and change each other in the doing of conceptual labor. From Tenets 5 and 6 we can see how these changes occur as a continuous dialogue. The section Conceptual Labor Analysis demonstrated how this conversation can produce a working model which is continuously redefined as its components change. Such models guide our labor on a cyclical path, which reflects back on itself as a way of progressing, like a traveller comparing their map to their surroundings as they travel.

The previous two concepts are the key to this cycle. Models are self-referential enough to continuously update their own terms, but when a model includes a conscious actor, it means someone is experiencing this process and attempting to describe, define, or at least comprehend it as they do.

Let us imagine an idealized version of this cycle in which the components of a model take turns to change. First, the actor approaches a project with a certain model in mind and does work to affect an outcome. The first component to change is work, as the actor does it. As the work changes, the context is next to change. This is because the relevant context of a model includes the specific conditions of work — ie its state of completion or the results of one’s recent actions.

When the actor notices the change to the context as it absorbs the change in work, they themselves change, whether it is in their thoughts, reactions, or, ultimately, in the model they hold in their head. At this point the cycle begins anew as the actor does the work of understanding or responding to the new state of the model.